Interfaith Cooperation in History? Lessons from the Past

By Claribel Low

What lessons can history offer us about interfaith dialogue, cooperation and conflict? Professor Peter Frankopan, Professor of Global History at Oxford University and UNESCO Professor of Silk Roads Studies at King’s College, Cambridge; explored this question in a closed-door roundtable discussion organised by the Social Cohesion Research Programme (SCRP) on 16 October 2025. Titled “Interfaith Cooperation in History? Lessons from the Past”, the hybrid session was attended by 70 participants comprising academics, community leaders and policymakers.

In his lecture, Professor Frankopan surveyed case studies of harmonious interfaith coexistence and cooperation across various historical epochs. Specifically, he examined the ancient Roman empire, Dunhuang as well as Islamic Spain, all of which, he argued, provided rich lessons for convivial living among those of different faiths.

When discussing interfaith conflicts, he emphasised that such conflicts might not necessarily be purely religious in nature, but rather, are oftentimes driven by underlying factors stemming from power and resource inequalities. Research has shown that economic compression and climate anomalies, for example, are significant stressors that can heighten anxiety and propel communities to persecute religious others more intently.

The discussion concluded with a lively Q&A session moderated by Dr Leong Chan-Hoong, Senior Fellow and Head of SCRP. Professor Frankopan urged the audience to critically assess dominant narratives and consider examples that might suggest an account to the contrary. For instance, despite deepening fissures and divisions in some parts of the world, there are just as many examples of multicultural communities living harmoniously.

Concluding the session, he acknowledged that there is no one-size-fits-all formula that can be applied across all contexts to prevent conflicts. However, he believes it is essential that memories of tolerance and harmonious coexistence are kept alive; once lost, these memories cannot be easily restored. It is perhaps for this very reason that the study of history must be kept thriving, so that it can serve as a mirror for us to reflect upon and learn from.

Historical Lessons for a Planet in Crisis: Peter Frankopan on The Earth Transformed

By Pey Peili

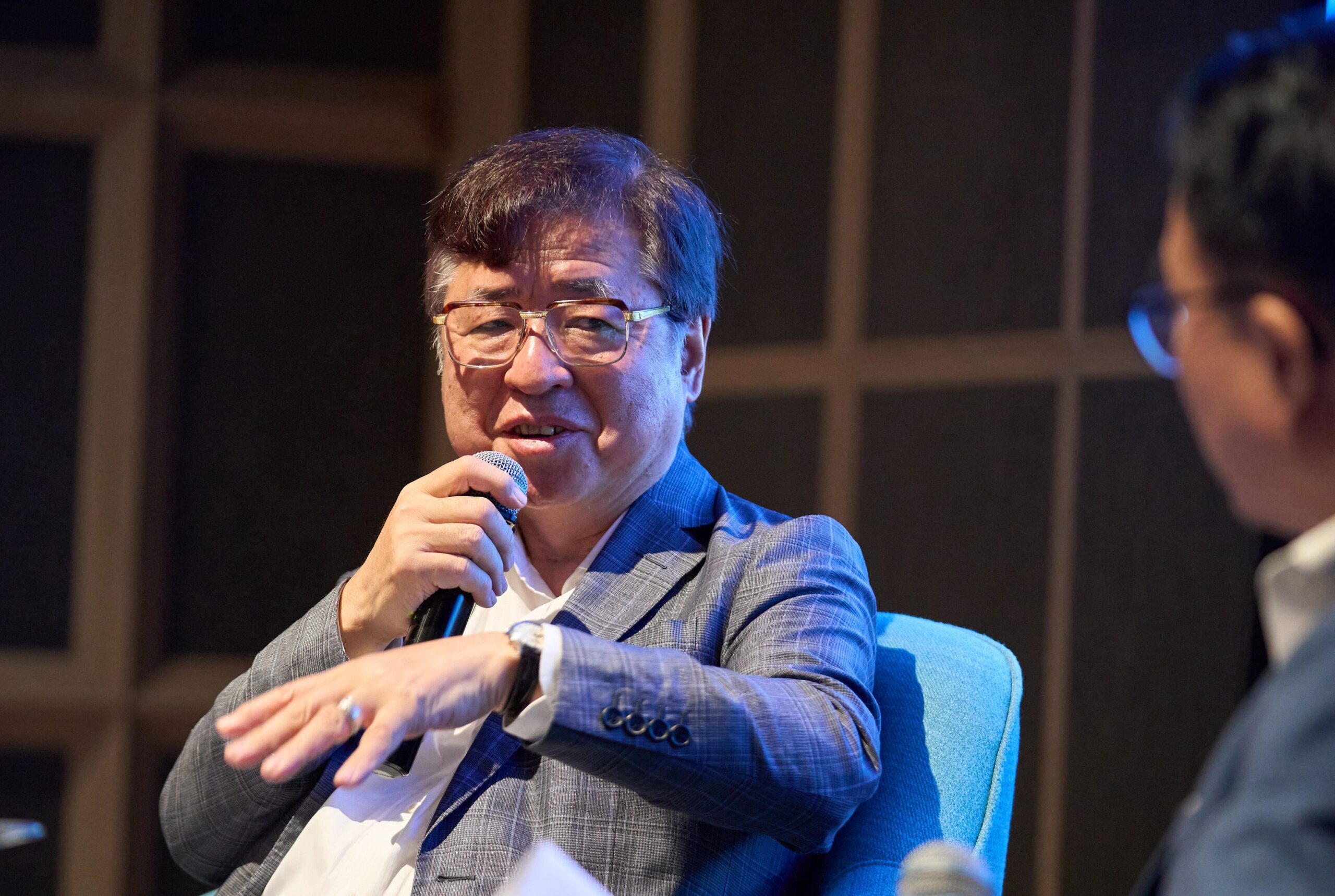

(L-R) Professor Peter Frankopan with Prof Mely Caballero-Anthony as moderator

Professor Peter Frankopan spoke at an RSIS seminar titled “Past as Prologue: Historical Lessons from “The Earth Transformed” for Contemporary Climate and Planetary Health Security”, based on his recent book The Earth Transformed. Professor Frankopan, a renowned historian from Oxford University and an S.T. Lee Distinguished Speaker at RSIS, presented a compelling case for re-evaluating history through an environmental lens.

Professor Frankopan argued that traditional historical study is often too human-centric, overlooking the fundamental roles of geology, geography, and climate. His work posits that the natural environment and climatic shifts have frequently been the primary drivers of political change, societal collapse, and civilisational transformation.

Spanning deep and extensive history, the talk illustrated how geology dictates resource location, which in turn shapes everything from centres of urbanisation to modern soft power. Professor Frankopan explored multiple case studies in his seminar, highlighting key events where climatic challenges drove social and economic instability, which brought about major changes to civilisation. These include the fall of Rome (climatic stress pushing the Huns westward), the collapse of the Maya civilisation (linked to multi-decade droughts), and the American War of Independence (tied to Caribbean hurricanes that created new economic opportunities).

He connected these historical precedents to the “uncharted territory” of the present day, highlighting accelerating crises such as rising sea temperatures, ice loss, and air pollution, which has caused 135 million premature deaths globally in the last four decades. He noted the specific vulnerabilities facing Singapore, which include significant sea-level rise and increasing heat waves.

The seminar concluded with a vibrant Q&A session, addressing topics such as the lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, the future of climate-induced migration, geoengineering, and the growing challenge of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) in a world of compounding catastrophes.

The Silk Roads: Lessons in Religious Diversity and Cohesion from the Heart of Central Asia

By Harith Hasanain

In an insightful and characteristically engaging seminar held on 14 October 2025, Professor Peter Frankopan reimagined the Silk Roads as vibrant networks of human connection that shaped the course of global history. Far from the romantic image of a single route linking China to Rome, he described a complex web of exchanges over land and sea that carried not just silk and spices but ideas, faiths, languages, fashions, music, and technologies across the vast spaces of Central Asia, the true “heart of the world”.

Tracing how the modern notion of the Silk Roads emerged, he explained that it was Japanese scholars in the late 19th and early 20th centuries who revived the term to highlight Asia’s central role in world history, particularly after Japan’s defeat of Russia in 1905. In the aftermath of World War II, the Silk Road ideal evolved into a symbol of peace and intercultural dialogue, gaining institutional form through UNESCO’s Silk Roads Programme in 1988. By the early 21st century, the concept resurfaced in Western and Chinese diplomacy, from the US ‘Silk Road Act’ to China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’.

At the heart of Professor Frankopan’s talk was how religions travelled and spread through these routes. Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism expanded through trade corridors, borrowing and blending as they went from Greco-Buddhist sculptures in Gandhara to early Islamic mosques modeled on Roman designs. Yet, networks and connections came not only with prosperity and ideas but also vulnerability: these same routes that spread culture and creativity also carried disease and plague, binding humanity through both brilliance and fragility.

Professor Frankopan devoted particular attention to religious diversity and cohesion, describing Central Asia as a crucible where belief systems coexisted, competed, and evolved. He showed how early empires built bridges between faiths, incorporating shared values of compassion, virtue, and coexistence. From the fusion of Buddhist and Hellenistic iconography to Islamic art celebrating Christian themes, these interactions reflected an enduring human search for meaning through dialogue rather than division.

To conclude, Professor Frankopan contrasted Asia’s long history of collaboration with Europe’s centuries of conflict, suggesting that the Silk Roads remind us that our greatest achievements, just like our gravest challenges, have always been shared.