11 March 2025

- RSIS

- Publication

- RSIS Publications

- IP25028 | Hegemonic Denial: Explaining Prabowo’s Foreign Policy

SYNOPSIS

Addressing doubts whether Prabowo Subianto is deviating from Indonesia’s “free and active” foreign policy, Yohanes Sulaiman argues that the president’s foreign policy is not that much different from Indonesia’s long-standing grand strategy — or the foreign policies of similar middle powers.

COMMENTARY

Since his inauguration on 20 October 2024, Indonesian president Prabowo Subianto has been making waves in international affairs. One of his most surprising acts was signing a joint statement with China, which sparked debate whether he was acknowledging China’s nine-dash claim in the South China Sea, something no Indonesian leader had done before. Indonesia’s long-standing position has been to deny that there is an overlapping claim with China in the South China Sea. Another move was Prabowo’s decision to join BRICS, a multilateral organisation that is seen as a counterweight to the prevalence of Western-dominated international organisations. At the same time, his commitment to ASEAN was questioned by some, particularly when Indonesian foreign minister Sugiono skipped the informal ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Bangkok in December 2024.

Some analysts believe Prabowo’s foreign policy moves during his first few months in office ignore decades of Indonesia’s “independent and active” foreign policy, which emphasises Indonesia’s desire not to pick policies that would give opportunities to other great powers to expand their influence in the region. Due to Indonesia’s geostrategic importance, the country is able to temporise whenever it faces pressure from other states.

Sugiono defended Prabowo’s aforesaid actions, arguing that joining BRICS was a manifestation of Indonesia’s independent and active foreign policy, was economically beneficial, and was a personal accomplishment of Prabowo’s. He also noted that the joint statement with China was a way of enhancing cooperation with neighbouring countries for the benefit of Indonesia. However, many respected Indonesian foreign policy experts demurred, arguing that signing it was simply motivated by economic interests and broke Indonesia’s long existing foreign policy principles.

I argue that while Prabowo’s actions may be seen as lacking “a considered policy foundation in both form and substance“, they do in fact still fall within Indonesia’s grand strategy, which is based on how Indonesia, as a middle power, views threats and on its satisfaction with the prevailing international order.

The Logic of Middle Powers’ Foreign Policy

To understand Indonesia’s foreign policy, I propose a new way of understanding and predicting the foreign policy of middle powers. Here, I employ Holbraad’s definition of a middle power, i.e., a state that has significant power to influence the region, yet is too weak to challenge the great powers directly. Essentially, a big fish in a small pond in the region where it resides.

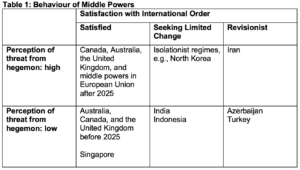

Middle powers can be classified on the basis of their interests and goals, which depend on two variables: (i) how satisfied they are with the international order — international order defined as the body of rules, norms, and institutions that govern relations among the key players in the international environment — and (ii) the extent to which they perceive the hegemon to be a threat.

A Typology of Middle Powers

Not all middle powers are happy with the current international order. To quote Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” So, all middle powers are alike, perpetuating international norms, rules, and order, but each unhappy middle power is unhappy in its own way.

Satisfied middle power states benefit from the current international order and the protection of the hegemonic power, leading them to support the hegemon in maintaining international stability. Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom exemplify such “happy” middle powers. They maintain cooperative relationships with the United States and support its foreign policy and security goals. While there may be ups and downs in their relationship with the United States as the hegemonic power, by and large they can be relied upon by the United States to support its foreign policy and security goals, especially in preserving the current international order. Thus, they are all alike in terms of their foreign and security policies.

Some satisfied middle powers are committed to maintaining the prevailing international order to some degree, but they do not trust the hegemonic power enough to heed its wishes unquestioningly. Hence, they maintain ambivalent relations with the dominant power.

Unhappy middle powers, however, are unhappy in their own ways. They pursue distinct foreign policies to safeguard their security and carve out their own limited version of the international order.

Those among them that believe the hegemon is a serious threat will behave far more aggressively to confront the threat, seeing that the lack of urgency will end up undermining their security. On the other hand, states that do not believe the main hegemon is a threat will be far more willing to cooperate with the hegemon or, when facing problems, will simply stall or hedge.

What is Hegemonic Denial?

Some unhappy states want some changes in the international order, yet, due to their geographical positions and relative power, simply do not have the means to force any change. As a result, their goal is limited — either to carve out their own sphere of influence in the region or to pursue isolationist policies that they believe will preserve their power. Other unhappy states have much broader objectives, thanks to the lower structural constraints they face, i.e., the fact that are surrounded by weak or non-aggressive states.

Unhappy middle powers challenge the dominance of the hegemonic power in their respective regions by pursuing a range of foreign policies. These middle powers aim to strengthen their regional positions in order to minimise the influence of stronger powers, a strategy known as “hegemonic denial”. Such states may pursue balancing strategies, such as by aligning with less threatening outside powers. They may build up their military strength to intimidate smaller states in their region or forge a coalition with regional actors that share their interests. The ultimate goal of all these strategies is to deny any great power the ability to threaten the middle power’s position in the region.

The above typology of middle powers, based on their perception of threat from the hegemon and attitudes towards the international order, can be summed up in Table 1.

The table shows that it is only with the assumption of power by Donald Trump in Washington earlier this year that there have been cases where satisfied states ended up seeing the hegemon as a threat. While it is too early to say whether this trend is just a hiccup or a long-term trend, the model predicts that those states will still try to preserve international norms and orders. The most probable action they would undertake is to strengthen their own grouping so that they can maintain the international order that they believe the hegemon is wrecking.

Examples of States Practising Hegemonic Denial

States like North Korea are middle powers that see the hegemon as their main threat and therefore dislike the hegemon-led international order, which they believe is detrimental to their positions. North Korea cannot change the existing order since it is surrounded by strong powers, notably Russia, China, South Korea, and Japan. All it can do is to isolate itself and adopt opportunistic policies with the main goal of preserving the Kim dynasty.

Iran, a revisionist state, sees the United States as a major threat. Iran is surrounded by weak states, such as Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, or middle powers that are strong enough but unwilling to directly confront it. As a result, it has the leeway to expand its influence throughout the region, such as by building a Shi’a crescent, an Iran-led movement comprising Hizballah, Hamas, the Houthis of Yemen, and various paramilitary groups in Iraq. Iran believes that by controlling those groups, it can check the United States and Israel, the United States’ main ally in the region.

Turkey is an example of a revisionist states that wishes to change the status quo to its benefit but at the same time does not see the United States as the main threat to its interests. Thus, it tries to expand its influence in the Middle East but is careful not to tread on the United States’ interests so to avoid causing friction in their relations.

Low Threat Perception; Moderate Change Sought

Indonesia and India are the quintessential big fishes in a small pond. They both are big and strong enough to influence their respective regions, yet they are too weak to prevent outside great powers, notably the United States and China, from influencing those regions. At the same time, neither of them sees the United States as an imminent threat to its interests. As a result, they are able to craft their own niche in their respective regions. In India’s case, it tries to be a key player in the US-led international order and at the same time engages in the so-called alternative order, notably the China-dominated BRICS. It also tries to counter China’s growing influence in its neighbouring countries, notably, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

In Indonesia’s case, since 1967, it has been trying to unite Southeast Asia under ASEAN, which serves as a vehicle for Indonesia’s leadership. Facing growing competition between the United States and China in the region, it pursues the policy of dynamic equilibrium, trying to accommodate the interests of both powers in the hope that they will recognise and strengthen Indonesia’s regional leadership.

Whither Prabowo’s Foreign Policy?

To sum up, Prabowo’s foreign policy, notably his quest to become the leader — or at least the representative — of the Global South fits with the hegemonic denial model. It is basically the policy of a leader who is trying to expand his country’s influence without undermining the international order. Even when Prabowo seemingly undermined the international order by agreeing to China’s declaration that there was an overlapping claim in the South China Sea, his foreign ministry immediately denied that there was a change in Indonesia’s official position. Also, in joining BRICS, Indonesia has no wish to undermine the current international order.

Still, one question remains. While Prabowo and Indonesia’s approach in general may work well at the moment, what will happen when tensions between China and the United States increase? While Indonesia at this point may be seen as hedging, the problem is that a hedge is still a hedge, and policy choices need to be made when it comes to the crunch. Will Indonesia’s strategy change at that point?

Yohanes Sulaiman was a Visiting Fellow with the Indonesia Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). He is an Associate Professor of International Relations at Universitas Jenderal Achmad Yani, Indonesia.

SYNOPSIS

Addressing doubts whether Prabowo Subianto is deviating from Indonesia’s “free and active” foreign policy, Yohanes Sulaiman argues that the president’s foreign policy is not that much different from Indonesia’s long-standing grand strategy — or the foreign policies of similar middle powers.

COMMENTARY

Since his inauguration on 20 October 2024, Indonesian president Prabowo Subianto has been making waves in international affairs. One of his most surprising acts was signing a joint statement with China, which sparked debate whether he was acknowledging China’s nine-dash claim in the South China Sea, something no Indonesian leader had done before. Indonesia’s long-standing position has been to deny that there is an overlapping claim with China in the South China Sea. Another move was Prabowo’s decision to join BRICS, a multilateral organisation that is seen as a counterweight to the prevalence of Western-dominated international organisations. At the same time, his commitment to ASEAN was questioned by some, particularly when Indonesian foreign minister Sugiono skipped the informal ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Bangkok in December 2024.

Some analysts believe Prabowo’s foreign policy moves during his first few months in office ignore decades of Indonesia’s “independent and active” foreign policy, which emphasises Indonesia’s desire not to pick policies that would give opportunities to other great powers to expand their influence in the region. Due to Indonesia’s geostrategic importance, the country is able to temporise whenever it faces pressure from other states.

Sugiono defended Prabowo’s aforesaid actions, arguing that joining BRICS was a manifestation of Indonesia’s independent and active foreign policy, was economically beneficial, and was a personal accomplishment of Prabowo’s. He also noted that the joint statement with China was a way of enhancing cooperation with neighbouring countries for the benefit of Indonesia. However, many respected Indonesian foreign policy experts demurred, arguing that signing it was simply motivated by economic interests and broke Indonesia’s long existing foreign policy principles.

I argue that while Prabowo’s actions may be seen as lacking “a considered policy foundation in both form and substance“, they do in fact still fall within Indonesia’s grand strategy, which is based on how Indonesia, as a middle power, views threats and on its satisfaction with the prevailing international order.

The Logic of Middle Powers’ Foreign Policy

To understand Indonesia’s foreign policy, I propose a new way of understanding and predicting the foreign policy of middle powers. Here, I employ Holbraad’s definition of a middle power, i.e., a state that has significant power to influence the region, yet is too weak to challenge the great powers directly. Essentially, a big fish in a small pond in the region where it resides.

Middle powers can be classified on the basis of their interests and goals, which depend on two variables: (i) how satisfied they are with the international order — international order defined as the body of rules, norms, and institutions that govern relations among the key players in the international environment — and (ii) the extent to which they perceive the hegemon to be a threat.

A Typology of Middle Powers

Not all middle powers are happy with the current international order. To quote Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” So, all middle powers are alike, perpetuating international norms, rules, and order, but each unhappy middle power is unhappy in its own way.

Satisfied middle power states benefit from the current international order and the protection of the hegemonic power, leading them to support the hegemon in maintaining international stability. Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom exemplify such “happy” middle powers. They maintain cooperative relationships with the United States and support its foreign policy and security goals. While there may be ups and downs in their relationship with the United States as the hegemonic power, by and large they can be relied upon by the United States to support its foreign policy and security goals, especially in preserving the current international order. Thus, they are all alike in terms of their foreign and security policies.

Some satisfied middle powers are committed to maintaining the prevailing international order to some degree, but they do not trust the hegemonic power enough to heed its wishes unquestioningly. Hence, they maintain ambivalent relations with the dominant power.

Unhappy middle powers, however, are unhappy in their own ways. They pursue distinct foreign policies to safeguard their security and carve out their own limited version of the international order.

Those among them that believe the hegemon is a serious threat will behave far more aggressively to confront the threat, seeing that the lack of urgency will end up undermining their security. On the other hand, states that do not believe the main hegemon is a threat will be far more willing to cooperate with the hegemon or, when facing problems, will simply stall or hedge.

What is Hegemonic Denial?

Some unhappy states want some changes in the international order, yet, due to their geographical positions and relative power, simply do not have the means to force any change. As a result, their goal is limited — either to carve out their own sphere of influence in the region or to pursue isolationist policies that they believe will preserve their power. Other unhappy states have much broader objectives, thanks to the lower structural constraints they face, i.e., the fact that are surrounded by weak or non-aggressive states.

Unhappy middle powers challenge the dominance of the hegemonic power in their respective regions by pursuing a range of foreign policies. These middle powers aim to strengthen their regional positions in order to minimise the influence of stronger powers, a strategy known as “hegemonic denial”. Such states may pursue balancing strategies, such as by aligning with less threatening outside powers. They may build up their military strength to intimidate smaller states in their region or forge a coalition with regional actors that share their interests. The ultimate goal of all these strategies is to deny any great power the ability to threaten the middle power’s position in the region.

The above typology of middle powers, based on their perception of threat from the hegemon and attitudes towards the international order, can be summed up in Table 1.

The table shows that it is only with the assumption of power by Donald Trump in Washington earlier this year that there have been cases where satisfied states ended up seeing the hegemon as a threat. While it is too early to say whether this trend is just a hiccup or a long-term trend, the model predicts that those states will still try to preserve international norms and orders. The most probable action they would undertake is to strengthen their own grouping so that they can maintain the international order that they believe the hegemon is wrecking.

Examples of States Practising Hegemonic Denial

States like North Korea are middle powers that see the hegemon as their main threat and therefore dislike the hegemon-led international order, which they believe is detrimental to their positions. North Korea cannot change the existing order since it is surrounded by strong powers, notably Russia, China, South Korea, and Japan. All it can do is to isolate itself and adopt opportunistic policies with the main goal of preserving the Kim dynasty.

Iran, a revisionist state, sees the United States as a major threat. Iran is surrounded by weak states, such as Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, or middle powers that are strong enough but unwilling to directly confront it. As a result, it has the leeway to expand its influence throughout the region, such as by building a Shi’a crescent, an Iran-led movement comprising Hizballah, Hamas, the Houthis of Yemen, and various paramilitary groups in Iraq. Iran believes that by controlling those groups, it can check the United States and Israel, the United States’ main ally in the region.

Turkey is an example of a revisionist states that wishes to change the status quo to its benefit but at the same time does not see the United States as the main threat to its interests. Thus, it tries to expand its influence in the Middle East but is careful not to tread on the United States’ interests so to avoid causing friction in their relations.

Low Threat Perception; Moderate Change Sought

Indonesia and India are the quintessential big fishes in a small pond. They both are big and strong enough to influence their respective regions, yet they are too weak to prevent outside great powers, notably the United States and China, from influencing those regions. At the same time, neither of them sees the United States as an imminent threat to its interests. As a result, they are able to craft their own niche in their respective regions. In India’s case, it tries to be a key player in the US-led international order and at the same time engages in the so-called alternative order, notably the China-dominated BRICS. It also tries to counter China’s growing influence in its neighbouring countries, notably, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

In Indonesia’s case, since 1967, it has been trying to unite Southeast Asia under ASEAN, which serves as a vehicle for Indonesia’s leadership. Facing growing competition between the United States and China in the region, it pursues the policy of dynamic equilibrium, trying to accommodate the interests of both powers in the hope that they will recognise and strengthen Indonesia’s regional leadership.

Whither Prabowo’s Foreign Policy?

To sum up, Prabowo’s foreign policy, notably his quest to become the leader — or at least the representative — of the Global South fits with the hegemonic denial model. It is basically the policy of a leader who is trying to expand his country’s influence without undermining the international order. Even when Prabowo seemingly undermined the international order by agreeing to China’s declaration that there was an overlapping claim in the South China Sea, his foreign ministry immediately denied that there was a change in Indonesia’s official position. Also, in joining BRICS, Indonesia has no wish to undermine the current international order.

Still, one question remains. While Prabowo and Indonesia’s approach in general may work well at the moment, what will happen when tensions between China and the United States increase? While Indonesia at this point may be seen as hedging, the problem is that a hedge is still a hedge, and policy choices need to be made when it comes to the crunch. Will Indonesia’s strategy change at that point?

Yohanes Sulaiman was a Visiting Fellow with the Indonesia Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). He is an Associate Professor of International Relations at Universitas Jenderal Achmad Yani, Indonesia.