20 May 2025

- RSIS

- Publication

- RSIS Publications

- IP25059 | An Early Assessment of Indonesia’s Defence Policy under Prabowo: Stylistic Changes; Directional Continuity

SYNOPSIS

Indonesia’s defence policy under President Prabowo Subianto exhibits stylistic departures from his predecessor’s approach, particularly through greater centralisation and direct presidential control. However, several key elements – especially in defence diplomacy, modernisation and military engagement in non-combat roles – suggest continuity with policies undertaken during his prior tenure as defence minister.

COMMENTARY

President Prabowo Subianto’s extensive military background and his previous tenure as Indonesia’s defence minister have led many observers to anticipate a more assertive and centralised approach to defence policymaking. The appointment of his long-time associate Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin – his classmate at the military academy and former colleague in the Army Special Forces – as minister of defence reinforces the perception of a tightly coordinated and personalised defence policy.

Prabowo’s centralised approach to defence policymaking marks a departure from the relatively hands-off style of President Joko Widodo. Nonetheless, several elements of continuity are evident in the substance of defence policy, particularly in Indonesia’s defence diplomacy, modernisation priorities and the military’s growing role in civilian sectors.

Omni-directional Defence Diplomacy

In his inaugural address, President Prabowo articulated a “good neighbour” policy, pledging to maintain good relations with all friendly states irrespective of geopolitical alignments. This articulation of Indonesia’s longstanding “independent and active” foreign policy doctrine has manifested in a series of recent defence diplomacy initiatives.

In November 2024, less than a month after Prabowo had been sworn into office, Indonesia held the inaugural joint naval exercise with the Russian Navy. While this bilateral exercise was unprecedented, it is consistent with Jakarta’s defence diplomacy engagement with Moscow in recent years, notably involving the hosting of the inaugural ASEAN-Russia joint naval exercise in 2021.

Simultaneously, Jakarta is renewing its defence ties with Beijing. Indonesia and China conducted limited-scale joint special-forces exercises under the “Sharp Knife” banner from 2011 until its suspension in 2015 following maritime rights disputes in the Natuna Sea. According to the Chinese embassy in Jakarta, bilateral military exercises formally resumed in December 2024, beginning with the “Heping Garuda” exercise focusing on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. Further indicators of deepening engagement between the two countries was evident in January this year when Defence Minister Sjamsoeddin met with General Liu Zhenli, chief of staff of the Joint Staff Department of China’s Central Military Commission, to discuss the possibility of joint military drills between the two countries, among others.

Despite these new engagements, Jakarta will continue to engage in defence diplomacy with long-standing partners such as the United States and Australia. Between 2003 and 2022, Indonesia participated in more than 100 joint exerciseswith the United States on top of routine military training and educational exchanges. High-profile multilateral exercises such as the Super Garuda Shield underscore the depth of these partnerships.

Indonesia’s defence diplomacy, therefore, reflects less a strategic pivot and more a broadening of defence diplomacy engagement – pursuing strategic autonomy by maintaining a balance across major powers, consistent with the nation’s foundational foreign policy principles.

Long-term Continuity in Defence Modernisation

A second area of policy continuity concerns Indonesia’s defence modernisation agenda. As minister of defence, Prabowo introduced Perisai Trisula Nusantara(Nusantara Trident Shield), a long-term defence modernisation programme to succeed the Minimum Essential Force (MEF) programme. The MEF was aimed at attaining the base defence capabilities necessary to safeguard Indonesia’s sovereignty by acquiring new, and upgrading outdated, defence equipment and enhancing inter-service interoperability.

During a parliamentary hearing in November 2024, Defence Minister Sjamsoeddin confirmed that the Prabowo administration would retain the Perisai Trisula Nusantara framework as the guiding blueprint for future modernisation efforts.

The programme’s overarching objective is to enhance Indonesia’s land, naval and air capabilities through major defence acquisitions. The tentative shopping list includes Rafale and F-15EX fighter jets, Scorpene submarines, Bora tactical ballistic missiles, BrahMos medium-range missiles, and the indigenously constructed “Red-White” frigates, among others. Several defence acquisition programmes, such as the Scorpene and Rafale deals, were initiated during Prabowo’s tenure as defence minister while others are in stages of negotiation or planning. Perisai Trisula Nusantara is projected to cost approximately US$125 billion over a 25-year period.

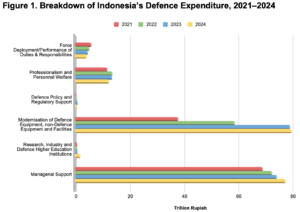

Defence spending patterns during Prabowo’s ministerial tenure offer a favourable outlook. Increasing capital expenditures, including defence procurement, have narrowed the gap with personnel expenditure (Figure 1) – an unprecedented shift in Indonesia’s defence budget structure. However, recent government spending cuts warrant caution. The 2025 budget refocusing resulted in a 16% reduction in the defence budget, and, if prolonged fiscal tightening is necessary, the long-term implementation of the modernisation agenda could be affected. Ministry of Defence officials have sought to allay such concerns by affirming that existing procurement contracts remain unaffected.

Sustained Military Involvement in Government Programmes

The Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI)’s involvement in civic missions and non-combat roles across sectors such as health, cyberspace and food security has been expanding since the Widodo era under the framework of “military operations other than war”. The TNI had signed dozens of memoranda of understanding with ministries, state agencies and local governments for its involvement in various civic missions. This trend appears poised to continue under President Prabowo.

For instance, Prabowo has instructed the TNI to assist with his administration’s food resiliency programmes, including the controversial food estate programme that the Ministry of Defence was put in charge of by President Widodo in July 2020. The TNI was deployed to help manage dedicated food estates throughout the country and tasked with various responsibilities such as ensuring the supply of fertilisers and agricultural machinery and field work coordination. The TNI is likely to retain these responsibilities under President Prabowo’s food resiliency programme.

The military has also been enlisted in Prabowo’s flagship policy – providing free nutritious meals to school-age children and pregnant women. The TNI has been enlisted in the programme and entrusted with three primary duties, including providing logistical support and facilitating food distribution; providing land and assisting the construction of service units at the local level; and monitoring and evaluating.

While the TNI’s ability to enhance policy delivery through its capacity for rapid mobilisation of its personnel and resources supports the convincing argument that its involvement is essential for the success of the Prabowo administration’s high-profile flagship policies, the TNI’s involvement is likely to go beyond these big-ticket items. For instance, as enshrined in Government Regulation No. 5/2025 on Forest Area Enforcement, the Prabowo administration will also deploy the TNI to efforts at countering illegal logging and illegal forestry operations.

Conclusion

The first six months of President Prabowo’s tenure as the commander-in-chief underscores a blend of assertive leadership and policy continuity, marked by centralised decision-making alongside sustained strategic priorities. While his administration has introduced stylistic changes, particularly through more direct presidential control over the defence policymaking agenda, in terms of substance, early indications suggest continuity with the policies pursued during Prabowo’s tenure as defence minister. This continuity is evident in the areas of defence diplomacy, military modernisation and involvement of the military for rapid and successful policy delivery in non-defence areas.

President Prabowo’s early defence policy reflects a deliberate effort to consolidate strategic autonomy while projecting stronger state capacity through the military. The continuity in defence modernisation and diplomacy suggests a pragmatic orientation that seeks to maximise Indonesia’s geopolitical flexibility amid intensifying great power rivalries.

At the same time, the expanding scope of the TNI’s “military operations other than war”, as evident in its involvement in the government’s non-defence policy areas, signals a deeper trend of securitisation that blurs the boundaries between the civilian and military domains. Indeed, there are some benefits in terms of improving policy delivery time and state responsiveness. However, if left unchecked, they could erode Indonesia’s already weak democratic oversight of the military and disincentivise civilian institutions to develop their capacities for policy delivery.

Keoni Marzuki is an independent researcher focusing on Indonesia’s foreign policy, defence policy and civil–military relations. He served as an adjunct lecturer at Parahyangan Catholic University’s Department of International Relations. He was previously an Associate Research Fellow with the Indonesia Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).

SYNOPSIS

Indonesia’s defence policy under President Prabowo Subianto exhibits stylistic departures from his predecessor’s approach, particularly through greater centralisation and direct presidential control. However, several key elements – especially in defence diplomacy, modernisation and military engagement in non-combat roles – suggest continuity with policies undertaken during his prior tenure as defence minister.

COMMENTARY

President Prabowo Subianto’s extensive military background and his previous tenure as Indonesia’s defence minister have led many observers to anticipate a more assertive and centralised approach to defence policymaking. The appointment of his long-time associate Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin – his classmate at the military academy and former colleague in the Army Special Forces – as minister of defence reinforces the perception of a tightly coordinated and personalised defence policy.

Prabowo’s centralised approach to defence policymaking marks a departure from the relatively hands-off style of President Joko Widodo. Nonetheless, several elements of continuity are evident in the substance of defence policy, particularly in Indonesia’s defence diplomacy, modernisation priorities and the military’s growing role in civilian sectors.

Omni-directional Defence Diplomacy

In his inaugural address, President Prabowo articulated a “good neighbour” policy, pledging to maintain good relations with all friendly states irrespective of geopolitical alignments. This articulation of Indonesia’s longstanding “independent and active” foreign policy doctrine has manifested in a series of recent defence diplomacy initiatives.

In November 2024, less than a month after Prabowo had been sworn into office, Indonesia held the inaugural joint naval exercise with the Russian Navy. While this bilateral exercise was unprecedented, it is consistent with Jakarta’s defence diplomacy engagement with Moscow in recent years, notably involving the hosting of the inaugural ASEAN-Russia joint naval exercise in 2021.

Simultaneously, Jakarta is renewing its defence ties with Beijing. Indonesia and China conducted limited-scale joint special-forces exercises under the “Sharp Knife” banner from 2011 until its suspension in 2015 following maritime rights disputes in the Natuna Sea. According to the Chinese embassy in Jakarta, bilateral military exercises formally resumed in December 2024, beginning with the “Heping Garuda” exercise focusing on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. Further indicators of deepening engagement between the two countries was evident in January this year when Defence Minister Sjamsoeddin met with General Liu Zhenli, chief of staff of the Joint Staff Department of China’s Central Military Commission, to discuss the possibility of joint military drills between the two countries, among others.

Despite these new engagements, Jakarta will continue to engage in defence diplomacy with long-standing partners such as the United States and Australia. Between 2003 and 2022, Indonesia participated in more than 100 joint exerciseswith the United States on top of routine military training and educational exchanges. High-profile multilateral exercises such as the Super Garuda Shield underscore the depth of these partnerships.

Indonesia’s defence diplomacy, therefore, reflects less a strategic pivot and more a broadening of defence diplomacy engagement – pursuing strategic autonomy by maintaining a balance across major powers, consistent with the nation’s foundational foreign policy principles.

Long-term Continuity in Defence Modernisation

A second area of policy continuity concerns Indonesia’s defence modernisation agenda. As minister of defence, Prabowo introduced Perisai Trisula Nusantara(Nusantara Trident Shield), a long-term defence modernisation programme to succeed the Minimum Essential Force (MEF) programme. The MEF was aimed at attaining the base defence capabilities necessary to safeguard Indonesia’s sovereignty by acquiring new, and upgrading outdated, defence equipment and enhancing inter-service interoperability.

During a parliamentary hearing in November 2024, Defence Minister Sjamsoeddin confirmed that the Prabowo administration would retain the Perisai Trisula Nusantara framework as the guiding blueprint for future modernisation efforts.

The programme’s overarching objective is to enhance Indonesia’s land, naval and air capabilities through major defence acquisitions. The tentative shopping list includes Rafale and F-15EX fighter jets, Scorpene submarines, Bora tactical ballistic missiles, BrahMos medium-range missiles, and the indigenously constructed “Red-White” frigates, among others. Several defence acquisition programmes, such as the Scorpene and Rafale deals, were initiated during Prabowo’s tenure as defence minister while others are in stages of negotiation or planning. Perisai Trisula Nusantara is projected to cost approximately US$125 billion over a 25-year period.

Defence spending patterns during Prabowo’s ministerial tenure offer a favourable outlook. Increasing capital expenditures, including defence procurement, have narrowed the gap with personnel expenditure (Figure 1) – an unprecedented shift in Indonesia’s defence budget structure. However, recent government spending cuts warrant caution. The 2025 budget refocusing resulted in a 16% reduction in the defence budget, and, if prolonged fiscal tightening is necessary, the long-term implementation of the modernisation agenda could be affected. Ministry of Defence officials have sought to allay such concerns by affirming that existing procurement contracts remain unaffected.

Sustained Military Involvement in Government Programmes

The Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI)’s involvement in civic missions and non-combat roles across sectors such as health, cyberspace and food security has been expanding since the Widodo era under the framework of “military operations other than war”. The TNI had signed dozens of memoranda of understanding with ministries, state agencies and local governments for its involvement in various civic missions. This trend appears poised to continue under President Prabowo.

For instance, Prabowo has instructed the TNI to assist with his administration’s food resiliency programmes, including the controversial food estate programme that the Ministry of Defence was put in charge of by President Widodo in July 2020. The TNI was deployed to help manage dedicated food estates throughout the country and tasked with various responsibilities such as ensuring the supply of fertilisers and agricultural machinery and field work coordination. The TNI is likely to retain these responsibilities under President Prabowo’s food resiliency programme.

The military has also been enlisted in Prabowo’s flagship policy – providing free nutritious meals to school-age children and pregnant women. The TNI has been enlisted in the programme and entrusted with three primary duties, including providing logistical support and facilitating food distribution; providing land and assisting the construction of service units at the local level; and monitoring and evaluating.

While the TNI’s ability to enhance policy delivery through its capacity for rapid mobilisation of its personnel and resources supports the convincing argument that its involvement is essential for the success of the Prabowo administration’s high-profile flagship policies, the TNI’s involvement is likely to go beyond these big-ticket items. For instance, as enshrined in Government Regulation No. 5/2025 on Forest Area Enforcement, the Prabowo administration will also deploy the TNI to efforts at countering illegal logging and illegal forestry operations.

Conclusion

The first six months of President Prabowo’s tenure as the commander-in-chief underscores a blend of assertive leadership and policy continuity, marked by centralised decision-making alongside sustained strategic priorities. While his administration has introduced stylistic changes, particularly through more direct presidential control over the defence policymaking agenda, in terms of substance, early indications suggest continuity with the policies pursued during Prabowo’s tenure as defence minister. This continuity is evident in the areas of defence diplomacy, military modernisation and involvement of the military for rapid and successful policy delivery in non-defence areas.

President Prabowo’s early defence policy reflects a deliberate effort to consolidate strategic autonomy while projecting stronger state capacity through the military. The continuity in defence modernisation and diplomacy suggests a pragmatic orientation that seeks to maximise Indonesia’s geopolitical flexibility amid intensifying great power rivalries.

At the same time, the expanding scope of the TNI’s “military operations other than war”, as evident in its involvement in the government’s non-defence policy areas, signals a deeper trend of securitisation that blurs the boundaries between the civilian and military domains. Indeed, there are some benefits in terms of improving policy delivery time and state responsiveness. However, if left unchecked, they could erode Indonesia’s already weak democratic oversight of the military and disincentivise civilian institutions to develop their capacities for policy delivery.

Keoni Marzuki is an independent researcher focusing on Indonesia’s foreign policy, defence policy and civil–military relations. He served as an adjunct lecturer at Parahyangan Catholic University’s Department of International Relations. He was previously an Associate Research Fellow with the Indonesia Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).