03 December 2025

- RSIS

- Publication

- RSIS Publications

- IP25112 | International Regulation of Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems: A Realistic Shift in Diplomatic Efforts

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• On 6 November 2025, the United Nations General Assembly’s First Committee passed its third consecutive resolution on lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS).

• Observers have criticised the 2025 resolution on LAWS as lacking ambition because it did not call on states to negotiate a legally binding arms control treaty and, unlike previous resolutions, it lacks a tangible outcome, such as organising informal consultations.

• Rather than viewing the 2025 resolution as unambitious, it should instead be seen as a realistic shift in diplomatic efforts aimed at achieving the long-term future regulation of LAWS.

COMMENTARY

On 6 November 2025, the United Nations General Assembly’s First Committee passed a resolution on lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS). This is the third consecutive resolution on LAWS passed by the First Committee.

A total of 156 states voted in favour of the resolution, while five states – the United States, Israel, Belarus, Russia and North Korea – voted against it. The resolution was tabled by Austria and co-sponsored by 30 states.

The resolution underscored the importance of a “comprehensive and inclusive multilateral approach” to address the challenges posed by LAWS, encompassing legal, technological, ethical, humanitarian and security considerations. It also noted the UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ call for states to commence negotiations on a legally binding arms control treaty on LAWS.

However, this year’s resolution did not call on states to commence negotiations and mandate informal consultations, unlike past resolutions. Instead, it encouraged states to “conduct further exchanges” without specifying the details of how they should be undertaken. In response, the Stop Killer Robots Campaign, a non-governmental organisation advocating for a legally binding arms control treaty on LAWS, expressed disappointment and characterised the resolution as lacking ambition.

Rather than viewing the 2025 resolution as unambitious, it should instead be seen as a realistic shift in diplomatic efforts aimed at achieving the long-term future regulation of LAWS.

By not calling on states to immediately begin negotiating a legally binding arms control treaty on LAWS, the resolution has created room to develop a middle ground between states calling for such a treaty and those resisting it. There is also an opportunity to secure buy-in among states that previously abstained from voting on the 2024 resolution, while retaining the support of states that backed previous LAWS resolutions.

Furthermore, by not mandating informal consultations, the resolution has addressed concerns regarding parallel diplomatic efforts on LAWS. States can now focus on upcoming discussions in 2026 at the Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on LAWS, the primary focal point so far for LAWS discussions.

A New Strategy to Achieve Multilateral Regulation of LAWS

The GGE on LAWS has been convened since 2016 under the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW), a key international humanitarian law instrument. Despite nearly a decade of meetings, progress has been slow, even on foundational issues. For instance, during this year’s GGE meetings, the group was still deliberating on how to define LAWS.

The GGE’s slow progress can be attributed to several factors, such as geopolitical friction and resistance to proposed measures intended to regulate LAWS. However, these are not unique to the GGE on LAWS and pose a challenge for several other multilateral fora as well.

Frustration with the GGE’s lack of progress has nevertheless led some states to believe that the group will fail to deliver on its mandate. Consequently, this prompted a desire to find a new avenue to discuss the regulation of LAWS. Austria has led these efforts through resolutions tabled at the UN General Assembly’s First Committee. For example, the 2024 resolution mandated informal consultations on LAWS to be held in New York in 2025. That resolution drew votes in favour from 161 states. However, during the informal consultations, Australia delivered a statement on behalf of 21 states, stating that “a process outside the GGE would take us backwards rather than forwards.”

The 2025 resolution, therefore, signals that the effort to find an alternative platform has not garnered sufficient support and that states prefer to use the GGE as the primary venue for LAWS discussions.

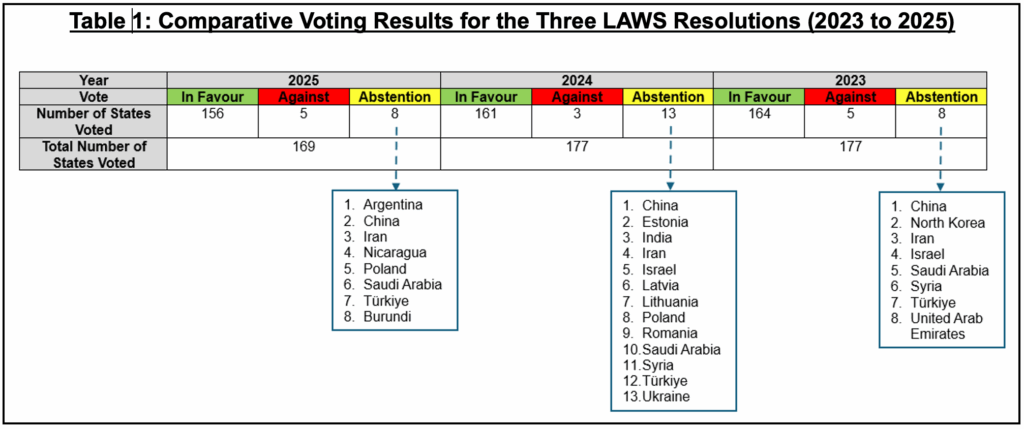

Moreover, by not calling on states to immediately begin negotiating a legally binding arms control treaty on LAWS, the resolution gained support from several states that had previously abstained from voting on the 2024 resolution, such as India, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania (Table 1).

The Baltic states’ support for the 2025 resolution is significant given that they face a common threat from Russia and have observed firsthand the growing importance of autonomy on the battlefield in Ukraine. India previously abstained from voting on the 2024 resolution due to concerns about parallel diplomatic efforts. The 2025 resolution alleviated this concern. Ukraine, on the other hand, did not vote on the 2025 resolution.

Despite objections against parallel diplomatic efforts concerning LAWS, the United States has consistently supported LAWS resolutions. Therefore, its decision to vote against the 2025 resolution marks a surprising departure from its previous stance. In explaining its vote, the United States stated that some of the language in the resolution did not reflect the consensus reached in the CCW. It described the informal consultation in New York as “not helpful” (despite its support for the 2024 resolution) and objected to the proposal to table a resolution on LAWS next year.

Looking Ahead to 2026

The GGE has to agree on a set of elements that could potentially form the basis of a future arms control treaty on LAWS as part of its report to the upcoming Seventh Review Conference of the CCW in November 2026.

Should the GGE fail to achieve this, the 2026 resolution on LAWS may see a return of efforts to seek a new avenue for LAWS discussions. Furthermore, it may call upon states to commence negotiating an international arms control treaty on LAWS outside of the CCW framework. A UN resolution on LAWS passed by the General Assembly could pave the way for a standalone arms control treaty, following the path set by the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Such a treaty could preserve the efforts made by the GGE, for instance, by incorporating the set of elements into the treaty text. However, establishing such a treaty may be challenging as it might not secure buy-in from states that have consistently maintained that the CCW is the most appropriate framework.

Mei Ching Liu is an Associate Research Fellow with the Military Transformations Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• On 6 November 2025, the United Nations General Assembly’s First Committee passed its third consecutive resolution on lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS).

• Observers have criticised the 2025 resolution on LAWS as lacking ambition because it did not call on states to negotiate a legally binding arms control treaty and, unlike previous resolutions, it lacks a tangible outcome, such as organising informal consultations.

• Rather than viewing the 2025 resolution as unambitious, it should instead be seen as a realistic shift in diplomatic efforts aimed at achieving the long-term future regulation of LAWS.

COMMENTARY

On 6 November 2025, the United Nations General Assembly’s First Committee passed a resolution on lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS). This is the third consecutive resolution on LAWS passed by the First Committee.

A total of 156 states voted in favour of the resolution, while five states – the United States, Israel, Belarus, Russia and North Korea – voted against it. The resolution was tabled by Austria and co-sponsored by 30 states.

The resolution underscored the importance of a “comprehensive and inclusive multilateral approach” to address the challenges posed by LAWS, encompassing legal, technological, ethical, humanitarian and security considerations. It also noted the UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ call for states to commence negotiations on a legally binding arms control treaty on LAWS.

However, this year’s resolution did not call on states to commence negotiations and mandate informal consultations, unlike past resolutions. Instead, it encouraged states to “conduct further exchanges” without specifying the details of how they should be undertaken. In response, the Stop Killer Robots Campaign, a non-governmental organisation advocating for a legally binding arms control treaty on LAWS, expressed disappointment and characterised the resolution as lacking ambition.

Rather than viewing the 2025 resolution as unambitious, it should instead be seen as a realistic shift in diplomatic efforts aimed at achieving the long-term future regulation of LAWS.

By not calling on states to immediately begin negotiating a legally binding arms control treaty on LAWS, the resolution has created room to develop a middle ground between states calling for such a treaty and those resisting it. There is also an opportunity to secure buy-in among states that previously abstained from voting on the 2024 resolution, while retaining the support of states that backed previous LAWS resolutions.

Furthermore, by not mandating informal consultations, the resolution has addressed concerns regarding parallel diplomatic efforts on LAWS. States can now focus on upcoming discussions in 2026 at the Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on LAWS, the primary focal point so far for LAWS discussions.

A New Strategy to Achieve Multilateral Regulation of LAWS

The GGE on LAWS has been convened since 2016 under the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW), a key international humanitarian law instrument. Despite nearly a decade of meetings, progress has been slow, even on foundational issues. For instance, during this year’s GGE meetings, the group was still deliberating on how to define LAWS.

The GGE’s slow progress can be attributed to several factors, such as geopolitical friction and resistance to proposed measures intended to regulate LAWS. However, these are not unique to the GGE on LAWS and pose a challenge for several other multilateral fora as well.

Frustration with the GGE’s lack of progress has nevertheless led some states to believe that the group will fail to deliver on its mandate. Consequently, this prompted a desire to find a new avenue to discuss the regulation of LAWS. Austria has led these efforts through resolutions tabled at the UN General Assembly’s First Committee. For example, the 2024 resolution mandated informal consultations on LAWS to be held in New York in 2025. That resolution drew votes in favour from 161 states. However, during the informal consultations, Australia delivered a statement on behalf of 21 states, stating that “a process outside the GGE would take us backwards rather than forwards.”

The 2025 resolution, therefore, signals that the effort to find an alternative platform has not garnered sufficient support and that states prefer to use the GGE as the primary venue for LAWS discussions.

Moreover, by not calling on states to immediately begin negotiating a legally binding arms control treaty on LAWS, the resolution gained support from several states that had previously abstained from voting on the 2024 resolution, such as India, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania (Table 1).

The Baltic states’ support for the 2025 resolution is significant given that they face a common threat from Russia and have observed firsthand the growing importance of autonomy on the battlefield in Ukraine. India previously abstained from voting on the 2024 resolution due to concerns about parallel diplomatic efforts. The 2025 resolution alleviated this concern. Ukraine, on the other hand, did not vote on the 2025 resolution.

Despite objections against parallel diplomatic efforts concerning LAWS, the United States has consistently supported LAWS resolutions. Therefore, its decision to vote against the 2025 resolution marks a surprising departure from its previous stance. In explaining its vote, the United States stated that some of the language in the resolution did not reflect the consensus reached in the CCW. It described the informal consultation in New York as “not helpful” (despite its support for the 2024 resolution) and objected to the proposal to table a resolution on LAWS next year.

Looking Ahead to 2026

The GGE has to agree on a set of elements that could potentially form the basis of a future arms control treaty on LAWS as part of its report to the upcoming Seventh Review Conference of the CCW in November 2026.

Should the GGE fail to achieve this, the 2026 resolution on LAWS may see a return of efforts to seek a new avenue for LAWS discussions. Furthermore, it may call upon states to commence negotiating an international arms control treaty on LAWS outside of the CCW framework. A UN resolution on LAWS passed by the General Assembly could pave the way for a standalone arms control treaty, following the path set by the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Such a treaty could preserve the efforts made by the GGE, for instance, by incorporating the set of elements into the treaty text. However, establishing such a treaty may be challenging as it might not secure buy-in from states that have consistently maintained that the CCW is the most appropriate framework.

Mei Ching Liu is an Associate Research Fellow with the Military Transformations Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).