21 April 2025

- RSIS

- Publication

- RSIS Publications

- India’s Path to Becoming a Developed Nation

SYNOPSIS

India aspires to be a developed nation by the time of the country’s 100th year of independence in 2047. Estimates are that the economy has to clock consistent growth of 8 per cent over the next 22 years to achieve a high-income status. Given the harsh global environment and India’s past growth record, this task is difficult but not impossible.

COMMENTARY

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has set a national aspiration for India to become a developed nation by the time of the country’s 100th year of independence in 2047. This raises two questions: What does it mean to be a developed nation, and can India achieve its aspiration? Both are interesting questions if also because they both defy binary answers.

A Large Economy but Still Poor

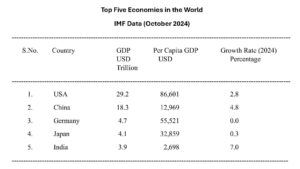

According to IMF data (October 2024), with a nominal GDP of US$3.9 trillion, India presently ranks fifth globally in terms of the size of the economy, behind America (US$29.2 trillion), China (US$18.3 trillion), Germany (US$4.7 trillion) and Japan (US$4.1 trillion). Many analysts estimate that under current trends, India will surpass Japan next year and Germany a year after that to become the third largest economy in the world. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

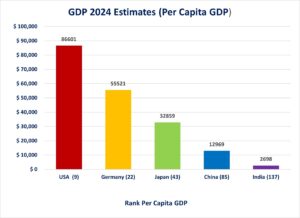

For India, that should be cause, maybe for cheer, but not celebration. India has a large economy for sure, but that’s primarily due to its large population. It is still a low middle-income country as per World Bank classification. With a per capita income of US$2,698 (IMF: October 2024), the country ranks 137th in the bottom third in the league of nations. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The IMF classifies a country as high-income when its per capita income reaches US$21,664. This means that India has to multiply its per capita income eightfold to break into the league of rich countries. The Government’s Economic Survey estimates that the economy has to grow at 8 per cent on a trot for the next 22 years to achieve that.

India’s Growth Record

How realistic is that possibility? Historical data will help. 1991 is considered a watershed year in India’s economic history because in that year, faced with a severe balance-of-payments crisis, the country struck a bold new path by giving up a dirigiste regime of licences and controls, embracing market-oriented economic management and opening up to the world.

In the over thirty years since then, the economy has grown by 8 per cent just seven times, but it could never sustain that pace for more than two consecutive years. The economy’s trend growth rate has certainly risen, but delivering a consistent growth of 8 per cent for the next 22 years will be a tall order.

India-China Hyphenation

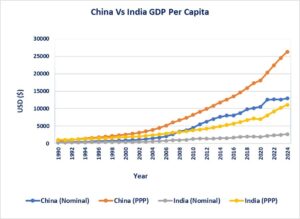

An India-China comparison is tempting and perhaps instructive when discussing economic performance. In 1990, India and China were at the same level in terms of per capita income. Since then, China has zoomed ahead, clocking double-digit growth on a trot for nearly three decades while India just lumbered along. Today, China’s GDP is more than four times India’s, while its per capita GDP is nearly five times India’s. Today, China is the world’s largest manufacturing and trading nation, whereas India’s global footprint in trade and manufacturing is still shallow. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Can India replicate the China model of manufacturing-led growth? That is a tantalising prospect but an unlikely one because the world in 1991, when China opened up, is very different from the world of today, when India wants to enter the global scene.

In 1990, globalisation was seen as a benign, win-win option. Today, led by the Trump tariffs, globalisation is on the retreat. The global value chains, the backbone of Chinese success, are crumbling. Also, in the 1990s, demand for manufacturing grew at a sizzling pace, whereas today, ageing populations in rich countries consume more services than goods.

India’s Growth Drivers

But India need not despair. It still has growth options. First, it has a large domestic market, which is an attraction for potential foreign investors. Second, even as demand for manufactures in the affluent world may decline, demand for services will grow. Digital technologies have now made it possible to deliver services from a distance, and India has a first-mover advantage here.

Moreover, as Arvind Panagariya of Columbia University argues in his book, India Unlimited, there is still a huge demand for low-wage goods even in a difficult world where global merchandise trade is under threat. India’s share in global trade is so small that even a small increase in share can mean a big gain.

But India cannot take success for granted. In particular, the country will not become a member of the high-income club under the “business as usual” model. What needs to be done to put the economy on a higher growth trajectory is familiar fare, but two points are worth emphasising.

Bridging Inequalities

First, mere growth will not do. India needs to ensure that the benefits of growth are widely shared, which is to say that the focus has to be on reducing inequality.

Inequalities are morally wrong and politically corrosive. They are also bad economics. India’s biggest growth driver is the huge consumption base of the bottom half of its population. If they earn more, they will spend more, which will in turn spur more production, more jobs and higher growth. If India’s development efforts can’t put more income into their pockets, it will be a huge missed opportunity.

While on the subject of inequality, it must be noted that it has more dimensions than just income. There needs to be a focus on education and health inequalities. World Bank Research shows that education has been the route for upward mobility across generations in poor societies. If additional efforts are not made to improve the quality of education in the vast hinterland of the country, an entire generation of children might forfeit the opportunity to move up the income ladder. Likewise, poor children suffer learning disadvantages because of malnutrition and the burden of disease, which calls for improvement in public health and primary health care.

Middle Income Trap

The second point on India’s path to a high-income status is the possibility of a middle-income trap. Development experience over the last 75 years has shown that countries find it relatively easy to transition from low to middle income but find it exceedingly difficult to graduate from middle to high income.

The middle-income trap is explained as follows: When a country is poor, it has a huge catch-up potential. Productivity goes up as labour moves from agriculture to industry, and the economy exploits the advantage of leapfrogging over several generations of technology to latch on to the latest. In contrast, movement from middle to high income becomes challenging as the low-hanging fruits are exhausted.

However, the middle-income trap is not an iron law. It can be overcome by focusing on innovation and intellectual property, which requires more brain power than muscle power. What needs to be done in this regard is again a large agenda, but the 1000-mile journey has to start with improving the quality of higher education, with much more emphasis on quality than quantity.

Governance Matters

In conclusion, it is worth noting that being a developed country means more than just being a rich country. High income is just one attribute of a developed country. As the noted political scientist Francis Fukuyama says, developed countries are characterised by three attributes – the rule of law, a strong state, and accountable governance. India can’t afford to ignore these in its aspiration to be a developed country by 2047.

About the Author

Dr Duvvuri Subbarao was the governor of the Reserve Bank of India from 2008 to 2013 and is currently a senior visiting fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.

SYNOPSIS

India aspires to be a developed nation by the time of the country’s 100th year of independence in 2047. Estimates are that the economy has to clock consistent growth of 8 per cent over the next 22 years to achieve a high-income status. Given the harsh global environment and India’s past growth record, this task is difficult but not impossible.

COMMENTARY

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has set a national aspiration for India to become a developed nation by the time of the country’s 100th year of independence in 2047. This raises two questions: What does it mean to be a developed nation, and can India achieve its aspiration? Both are interesting questions if also because they both defy binary answers.

A Large Economy but Still Poor

According to IMF data (October 2024), with a nominal GDP of US$3.9 trillion, India presently ranks fifth globally in terms of the size of the economy, behind America (US$29.2 trillion), China (US$18.3 trillion), Germany (US$4.7 trillion) and Japan (US$4.1 trillion). Many analysts estimate that under current trends, India will surpass Japan next year and Germany a year after that to become the third largest economy in the world. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

For India, that should be cause, maybe for cheer, but not celebration. India has a large economy for sure, but that’s primarily due to its large population. It is still a low middle-income country as per World Bank classification. With a per capita income of US$2,698 (IMF: October 2024), the country ranks 137th in the bottom third in the league of nations. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The IMF classifies a country as high-income when its per capita income reaches US$21,664. This means that India has to multiply its per capita income eightfold to break into the league of rich countries. The Government’s Economic Survey estimates that the economy has to grow at 8 per cent on a trot for the next 22 years to achieve that.

India’s Growth Record

How realistic is that possibility? Historical data will help. 1991 is considered a watershed year in India’s economic history because in that year, faced with a severe balance-of-payments crisis, the country struck a bold new path by giving up a dirigiste regime of licences and controls, embracing market-oriented economic management and opening up to the world.

In the over thirty years since then, the economy has grown by 8 per cent just seven times, but it could never sustain that pace for more than two consecutive years. The economy’s trend growth rate has certainly risen, but delivering a consistent growth of 8 per cent for the next 22 years will be a tall order.

India-China Hyphenation

An India-China comparison is tempting and perhaps instructive when discussing economic performance. In 1990, India and China were at the same level in terms of per capita income. Since then, China has zoomed ahead, clocking double-digit growth on a trot for nearly three decades while India just lumbered along. Today, China’s GDP is more than four times India’s, while its per capita GDP is nearly five times India’s. Today, China is the world’s largest manufacturing and trading nation, whereas India’s global footprint in trade and manufacturing is still shallow. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Can India replicate the China model of manufacturing-led growth? That is a tantalising prospect but an unlikely one because the world in 1991, when China opened up, is very different from the world of today, when India wants to enter the global scene.

In 1990, globalisation was seen as a benign, win-win option. Today, led by the Trump tariffs, globalisation is on the retreat. The global value chains, the backbone of Chinese success, are crumbling. Also, in the 1990s, demand for manufacturing grew at a sizzling pace, whereas today, ageing populations in rich countries consume more services than goods.

India’s Growth Drivers

But India need not despair. It still has growth options. First, it has a large domestic market, which is an attraction for potential foreign investors. Second, even as demand for manufactures in the affluent world may decline, demand for services will grow. Digital technologies have now made it possible to deliver services from a distance, and India has a first-mover advantage here.

Moreover, as Arvind Panagariya of Columbia University argues in his book, India Unlimited, there is still a huge demand for low-wage goods even in a difficult world where global merchandise trade is under threat. India’s share in global trade is so small that even a small increase in share can mean a big gain.

But India cannot take success for granted. In particular, the country will not become a member of the high-income club under the “business as usual” model. What needs to be done to put the economy on a higher growth trajectory is familiar fare, but two points are worth emphasising.

Bridging Inequalities

First, mere growth will not do. India needs to ensure that the benefits of growth are widely shared, which is to say that the focus has to be on reducing inequality.

Inequalities are morally wrong and politically corrosive. They are also bad economics. India’s biggest growth driver is the huge consumption base of the bottom half of its population. If they earn more, they will spend more, which will in turn spur more production, more jobs and higher growth. If India’s development efforts can’t put more income into their pockets, it will be a huge missed opportunity.

While on the subject of inequality, it must be noted that it has more dimensions than just income. There needs to be a focus on education and health inequalities. World Bank Research shows that education has been the route for upward mobility across generations in poor societies. If additional efforts are not made to improve the quality of education in the vast hinterland of the country, an entire generation of children might forfeit the opportunity to move up the income ladder. Likewise, poor children suffer learning disadvantages because of malnutrition and the burden of disease, which calls for improvement in public health and primary health care.

Middle Income Trap

The second point on India’s path to a high-income status is the possibility of a middle-income trap. Development experience over the last 75 years has shown that countries find it relatively easy to transition from low to middle income but find it exceedingly difficult to graduate from middle to high income.

The middle-income trap is explained as follows: When a country is poor, it has a huge catch-up potential. Productivity goes up as labour moves from agriculture to industry, and the economy exploits the advantage of leapfrogging over several generations of technology to latch on to the latest. In contrast, movement from middle to high income becomes challenging as the low-hanging fruits are exhausted.

However, the middle-income trap is not an iron law. It can be overcome by focusing on innovation and intellectual property, which requires more brain power than muscle power. What needs to be done in this regard is again a large agenda, but the 1000-mile journey has to start with improving the quality of higher education, with much more emphasis on quality than quantity.

Governance Matters

In conclusion, it is worth noting that being a developed country means more than just being a rich country. High income is just one attribute of a developed country. As the noted political scientist Francis Fukuyama says, developed countries are characterised by three attributes – the rule of law, a strong state, and accountable governance. India can’t afford to ignore these in its aspiration to be a developed country by 2047.

About the Author

Dr Duvvuri Subbarao was the governor of the Reserve Bank of India from 2008 to 2013 and is currently a senior visiting fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.