14 November 2025

- RSIS

- Publication

- RSIS Publications

- IP25107 | Keelung, 140 Years After the Sino-French War

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• 140 years ago, France and China went to war over control of northern Vietnam. Initially fought on land, the conflict soon expanded to the sea, with French forces launching an assault on northern Taiwan, in Keelung.

• Despite their technological superiority and limited military successes, French troops suffered heavy losses and failed to take control of the island.

• The historical lessons of this battle offer valuable tactical and strategic insights, highlighting the enduring complexity of any attempt to seize the island of Taiwan by force.

COMMENTARY

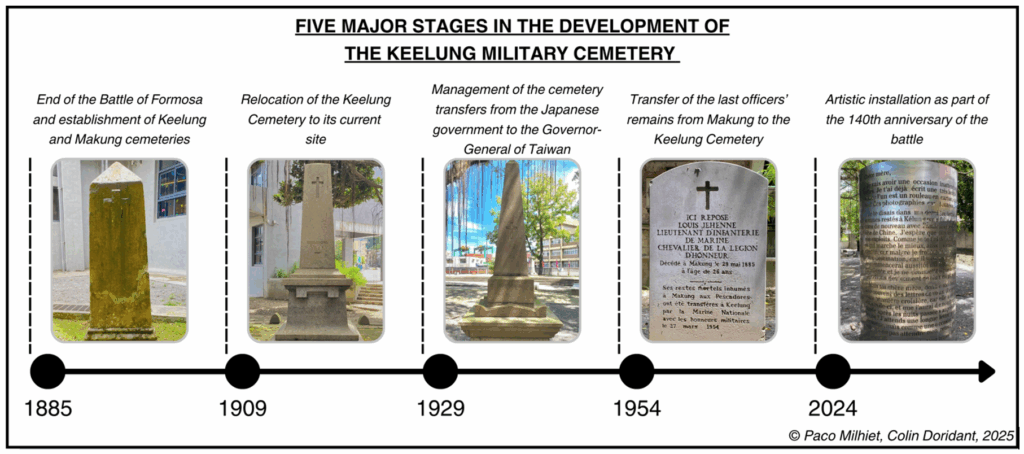

Every 11 November, a public holiday in France that commemorates the end of the First World War and honours all soldiers who died in overseas operations, the French Office in Taipei holds a discreet, yet solemn, ceremony at the French Cemetery in the coastal city of Keelung on the northern shore of Taiwan.

But why is there a French military cemetery 10,000 kilometres from Paris?

This site holds the graves of French soldiers who fell during the Sino-French War (1884–1885) – a conflict that pitted the forces of the French Third Republic against the Qing dynasty. The French military campaign on Taiwan was a deadly confrontation that claimed the lives of at least 700 French soldiers and several thousand Chinese combatants. It symbolises the brutal colonial war waged by France in Asia in its quest to control Indochina.

140 years later, the tombstones stand as silent witnesses to this violent episode – and as a reminder of the enduring strategic interest in controlling the island of Taiwan.

The Origin of the War: A Struggle to Control Northern Vietnam

France was a relative latecomer to Asia, compared with other European colonial powers such as Portugal, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Initiated at the end of the 17th century with an embassy to Siam, the French colonial ambition fully materialised in the 19th century – first on the Chinese mainland, where it sought commercial advantages comparable to those obtained by Britain through the Treaty of Nanking following the First Opium War (1839–1842).

During the Second Opium War (1856–1860), France played an active role. In December 1857, Franco-British troops captured the city of Guangzhou, which they occupied for four years. Soon, the Qing dynasty was forced to open 11 additional ports to foreign powers, authorise the establishment of embassies in Beijing, grant navigation rights on the Yangtze River, and allow foreigners freer movement within China. In October 1860, European allied forces marched on Beijing and looted the Summer Palace.

In parallel, the struggle for control over northern Vietnam further exacerbated tensions. Pursuing an active policy along the Mekong, France had established the colony of Cochinchina (southern Vietnam) in 1862, and sought to extend its influence into Tonkin (northern Vietnam) – a region historically under Chinese suzerainty. Although a series of unequal treaties signed in 1884 placed Annam and Tonkin under French protectorate, recurrent Chinese attacks on French interests reignited the conflict, which soon escalated and took on a maritime dimension. In August 1884, the Fujian Fleet and the Fuzhou Arsenal were destroyed by the French Navy.

The Conflict Extends to Formosa

The French forces then targeted the island of Formosa (Taiwan), to seize territorial leverage and force China into negotiations. Initially repelled at Keelung in late August 1884, French forces captured the city in early October but failed to take Tamsui. After a blockade of the island proved ineffective and the inland advance remained limited, reinforcements from Africa helped French troops to launch a renewed offensive in January 1885 on the heights above Keelung.

Despite the conquest of the Pescadores Islands in late March 1885, French troops were ravaged by cholera and typhoid epidemics. Faced with a tactical deadlock on Formosa and the opening of armistice negotiations, hostilities ceased in mid-April 1885. The campaign ended in a return to the status quo ante bellum.

In Tonkin, despite a tactical defeat at Lang Son, French forces ultimately prevailed. The Treaty of Tianjin, signed in June 1885, ended the war: China renounced any sovereign claim over Vietnam, while France withdrew from Formosa and returned the Pescadores. Two years later, in 1887, the Indochinese Union was officially formed, bringing together Cochinchina, Annam, Tonkin and Cambodia; Laos was added in 1899.

In the end, the Sino-French War laid the foundations of French Indochina, ushering in nearly a century of colonial rule in Southeast Asia.

Geopolitical Lessons for the 21st Century

As many analysts now discuss Beijing’s possible ambition to seize the island of Taiwan by force, the historical lessons of the French military campaign offer valuable tactical and strategic insights, highlighting the enduring complexity of such an operation.

Admittedly, the historical context was very different. In 1885, Taiwan was only a secondary objective for France, which primarily sought to weaken imperial China as part of its conquest of Indochina. The Qing dynasty, already in decline, was nearing the end of its rule. Yet, despite its clear technological superiority, the French expedition failed to establish a lasting presence on the island – a failure that underscored both the resilience of the local defenders and the limits of military power in a rugged, insular environment. During the battle, the French campaign was closely monitored by Japan – a rising regional power with its own ambitions toward the island. Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, who would later become Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy, visited Keelung during the French occupation.

While the US Army invasion planning in 1944 and recent war games favoured amphibious operations in the island’s south, the defence of the northern shore has remained central to Taiwan’s strategy, as evidenced by the annual Han Kuang exercises. In the July 2025 edition, the 99th Taiwanese Marine Brigade trained to redeploy rapidly from south to north and simulated a response to a People’s Liberation Army attempt to penetrate Taipei via the Tamsui River – the very manoeuvre the French Navy failed to execute 140 years earlier.

Thus, the French military campaign on Taiwan remains a geopolitical lesson with enduring relevance, embodied today by the French cemetery that still overlooks the harbour – bearing silent testimony to thwarted ambitions for control of this contested island.

Paco Milhiet is a Visiting Fellow with the South Asia Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. Colin Doridant is an analyst focusing on France’s relations with Asia.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• 140 years ago, France and China went to war over control of northern Vietnam. Initially fought on land, the conflict soon expanded to the sea, with French forces launching an assault on northern Taiwan, in Keelung.

• Despite their technological superiority and limited military successes, French troops suffered heavy losses and failed to take control of the island.

• The historical lessons of this battle offer valuable tactical and strategic insights, highlighting the enduring complexity of any attempt to seize the island of Taiwan by force.

COMMENTARY

Every 11 November, a public holiday in France that commemorates the end of the First World War and honours all soldiers who died in overseas operations, the French Office in Taipei holds a discreet, yet solemn, ceremony at the French Cemetery in the coastal city of Keelung on the northern shore of Taiwan.

But why is there a French military cemetery 10,000 kilometres from Paris?

This site holds the graves of French soldiers who fell during the Sino-French War (1884–1885) – a conflict that pitted the forces of the French Third Republic against the Qing dynasty. The French military campaign on Taiwan was a deadly confrontation that claimed the lives of at least 700 French soldiers and several thousand Chinese combatants. It symbolises the brutal colonial war waged by France in Asia in its quest to control Indochina.

140 years later, the tombstones stand as silent witnesses to this violent episode – and as a reminder of the enduring strategic interest in controlling the island of Taiwan.

The Origin of the War: A Struggle to Control Northern Vietnam

France was a relative latecomer to Asia, compared with other European colonial powers such as Portugal, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Initiated at the end of the 17th century with an embassy to Siam, the French colonial ambition fully materialised in the 19th century – first on the Chinese mainland, where it sought commercial advantages comparable to those obtained by Britain through the Treaty of Nanking following the First Opium War (1839–1842).

During the Second Opium War (1856–1860), France played an active role. In December 1857, Franco-British troops captured the city of Guangzhou, which they occupied for four years. Soon, the Qing dynasty was forced to open 11 additional ports to foreign powers, authorise the establishment of embassies in Beijing, grant navigation rights on the Yangtze River, and allow foreigners freer movement within China. In October 1860, European allied forces marched on Beijing and looted the Summer Palace.

In parallel, the struggle for control over northern Vietnam further exacerbated tensions. Pursuing an active policy along the Mekong, France had established the colony of Cochinchina (southern Vietnam) in 1862, and sought to extend its influence into Tonkin (northern Vietnam) – a region historically under Chinese suzerainty. Although a series of unequal treaties signed in 1884 placed Annam and Tonkin under French protectorate, recurrent Chinese attacks on French interests reignited the conflict, which soon escalated and took on a maritime dimension. In August 1884, the Fujian Fleet and the Fuzhou Arsenal were destroyed by the French Navy.

The Conflict Extends to Formosa

The French forces then targeted the island of Formosa (Taiwan), to seize territorial leverage and force China into negotiations. Initially repelled at Keelung in late August 1884, French forces captured the city in early October but failed to take Tamsui. After a blockade of the island proved ineffective and the inland advance remained limited, reinforcements from Africa helped French troops to launch a renewed offensive in January 1885 on the heights above Keelung.

Despite the conquest of the Pescadores Islands in late March 1885, French troops were ravaged by cholera and typhoid epidemics. Faced with a tactical deadlock on Formosa and the opening of armistice negotiations, hostilities ceased in mid-April 1885. The campaign ended in a return to the status quo ante bellum.

In Tonkin, despite a tactical defeat at Lang Son, French forces ultimately prevailed. The Treaty of Tianjin, signed in June 1885, ended the war: China renounced any sovereign claim over Vietnam, while France withdrew from Formosa and returned the Pescadores. Two years later, in 1887, the Indochinese Union was officially formed, bringing together Cochinchina, Annam, Tonkin and Cambodia; Laos was added in 1899.

In the end, the Sino-French War laid the foundations of French Indochina, ushering in nearly a century of colonial rule in Southeast Asia.

Geopolitical Lessons for the 21st Century

As many analysts now discuss Beijing’s possible ambition to seize the island of Taiwan by force, the historical lessons of the French military campaign offer valuable tactical and strategic insights, highlighting the enduring complexity of such an operation.

Admittedly, the historical context was very different. In 1885, Taiwan was only a secondary objective for France, which primarily sought to weaken imperial China as part of its conquest of Indochina. The Qing dynasty, already in decline, was nearing the end of its rule. Yet, despite its clear technological superiority, the French expedition failed to establish a lasting presence on the island – a failure that underscored both the resilience of the local defenders and the limits of military power in a rugged, insular environment. During the battle, the French campaign was closely monitored by Japan – a rising regional power with its own ambitions toward the island. Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, who would later become Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy, visited Keelung during the French occupation.

While the US Army invasion planning in 1944 and recent war games favoured amphibious operations in the island’s south, the defence of the northern shore has remained central to Taiwan’s strategy, as evidenced by the annual Han Kuang exercises. In the July 2025 edition, the 99th Taiwanese Marine Brigade trained to redeploy rapidly from south to north and simulated a response to a People’s Liberation Army attempt to penetrate Taipei via the Tamsui River – the very manoeuvre the French Navy failed to execute 140 years earlier.

Thus, the French military campaign on Taiwan remains a geopolitical lesson with enduring relevance, embodied today by the French cemetery that still overlooks the harbour – bearing silent testimony to thwarted ambitions for control of this contested island.

Paco Milhiet is a Visiting Fellow with the South Asia Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. Colin Doridant is an analyst focusing on France’s relations with Asia.