31 October 2019

- RSIS

- Publication

- RSIS Publications

- Political Populism: Eroding Asia’s Complex Interdependence?

SYNOPSIS

Asia’s regional order is increasingly vulnerable to the resurgence of political populism. Policy shifts in the United States and Europe alter incentives elsewhere, but political populism has also been on the rise in Asia. Populism is eroding political support in Asia for the region’s complex economic interdependence.

COMMENTARY

POLITICAL POPULISM is not new but has been increasing in prominence in recent years. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers and legal scholars saw it as a fatal flaw of democracy, which they saw as vulnerable to demagogic rhetoric mobilising the illiterate masses against identified “enemies of the people”.

Enlightenment liberals in the early United States and in Europe after the Napoleonic Wars drew on this tradition in seeking to constrain executive power with institutional checks and in asserting the rule of law for all to protect minority interests. Most recently, much attention has been devoted to the resurgence of populist politics in the West and the erosion of these inherited institutional and normative checks. This latest populist turn is also highly consequential for the Asian region and threatens one of its dominant characteristics − complex interdependence.

Political Populism and Disruption in Asia

Most obviously, political populism is typically associated with a nativist turn away from economic openness and the growing trade, investment and financial interdependence on which the Asian region collectively has relied as drivers of growth and prosperity. A second, related reason is that political populism has also been associated with a growing distrust of multilateral diplomacy and international institutions generally, as well as a tendency to defend narrower conceptions of national interest.

The Asian region exhibits highly complex forms of interdependence, but by comparison with the North Atlantic region and Western Europe in particular, these interdependencies are relatively loose and less deeply institutionalised. This has often been seen as having advantages of flexibility and efficiency, but as political populism reshapes the global order it may make Asia’s regional order more vulnerable to disruption.

The Trump administration’s sudden withdrawal from Syria and the current UK government’s last-ditch tactics in the ongoing Brexit negotiations are both symbolic of this shift as well as systemically consequential. Populist leaders are unlikely to coordinate in a new “populist internationale”, but the policy reorientation of the two powers most associated with the post-1945 “liberal order” has wider implications.

Turkey’s decision to invade northern Syria and the deterioration of Japan-South Korea relations are plausible examples. Both suggest that governments in longstanding US allies feel increasingly emboldened to depart from international behavioural norms in security and foreign policy. The US itself has long had a tendency to justify a mix of multilateralism with unilateral national measures, but the Trump administration’s much sharper emphasis on the latter alters the calculations of many other governments.

Varieties of Political Populism in Asia

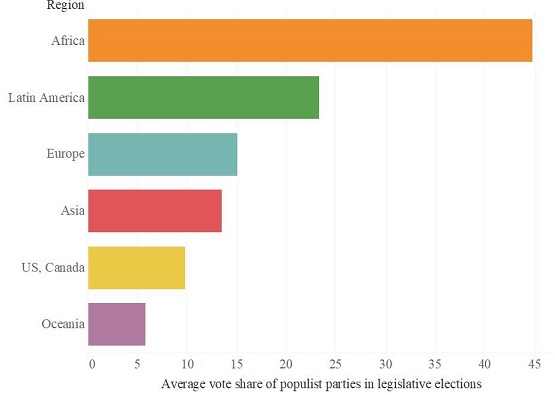

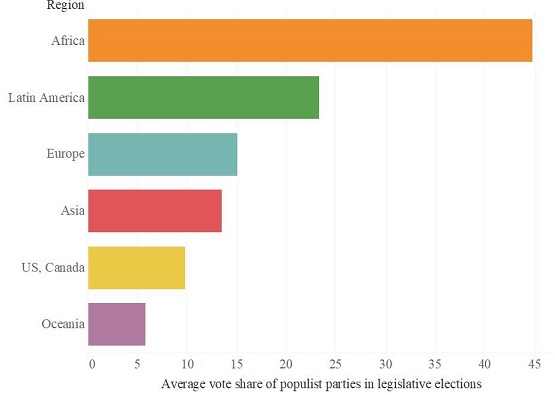

A third reason why political populism is consequential for Asia is that it is taking hold in important countries in the region, albeit in highly varied forms. Figure 1 illustrates the average vote share of populist parties by region in legislative elections since 20001. It shows that conceived broadly, populism in Asia has been nearly as successful as in Europe since the turn of the century.

This figure underestimates its importance in Asia, since the vote share of populist candidates in presidential elections is typically much higher (likely reflecting a tendency for populist parties to be dominated by charismatic leaders). For Asia since 2000, populist presidential candidates obtained an average vote share of 28%, with a rising trend over time.

Taking both legislative and presidential elections into account, the data indicate that political populism has been especially important in Indonesia, India, the Philippines, South Korea and Taiwan.

We are aware that characterisations of particular cases are often contested by specialists. Yet our dataset is unique in distinguishing different varieties of populism, identifying the primary “out-group(s)” that populist leaders and parties seek to target as enemies of the people.

Compared to Europe, Latin America and Oceania, Asian populism is rarely strongly anti-immigrant. More often, it targets domestic political elites (in legislative elections generally and in presidential elections in the Philippines), domestic ethnic groups (in Bangladesh, India and Taiwan) or foreign threats (in Pakistan, South Korea and especially Taiwan).

_______________________

1 The data are drawn from a populism coding project initiated by the University of Melbourne and including collaborators at the University of Cambridge, the LSE and RMIT (Melbourne). The dataset adopts an inclusive definition of populism, using a mixture of party manifestos, leader speeches, expert opinion and scholarly literature to identify candidates and parties that seek to mobilise political support based on a rhetorical dualism between the “people” and “elites” or other out-groups.

Figure 1: Average aggregated vote share for populist parties by major region in legislative elections, 2000-2019

Source: Global populism dataset, University of Cambridge/LSE/RMIT/University of Melbourne.

Political Populism and Political Nationalism

Regarding the latter, distinguishing political populism from more traditional forms of political nationalism can be particularly challenging. Clearly, some mainstream political parties also seek to deploy nationalism as a vote mobiliser (though it is not their dominant characteristic). This is conspicuously true for the ruling Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, which may be an important reason why populist parties there have been less successful than elsewhere.

The South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s centrist-liberal Democratic Party has also reflected and tactically deployed the considerable popular nationalist sentiment in South Korean society as he vowed in early August that in the escalating bilateral trade dispute the country would “never again lose to Japan”. More charitably, the demonstrated ability of populist parties in South Korea to tap into deep-seated nationalist sentiment may mean that mainstream parties find it difficult to avoid doing the same.

A similar phenomenon can be observed in the UK’s Conservative Party since 2016, where the success of populist movements and the associated UKIP and Brexit parties has driven the party towards an uncompromising “hard Brexit” position. Both developments underline the growing fragility of multilateralism in Europe and Asia and of the complex interdependence that it generated.

About the Author

Andrew Walter is NTUC Professor of International Economic Relations, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore and Professor of International Relations in the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Melbourne. His previous academic positions were at Oxford University and the London School of Economics and Political Science.

SYNOPSIS

Asia’s regional order is increasingly vulnerable to the resurgence of political populism. Policy shifts in the United States and Europe alter incentives elsewhere, but political populism has also been on the rise in Asia. Populism is eroding political support in Asia for the region’s complex economic interdependence.

COMMENTARY

POLITICAL POPULISM is not new but has been increasing in prominence in recent years. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers and legal scholars saw it as a fatal flaw of democracy, which they saw as vulnerable to demagogic rhetoric mobilising the illiterate masses against identified “enemies of the people”.

Enlightenment liberals in the early United States and in Europe after the Napoleonic Wars drew on this tradition in seeking to constrain executive power with institutional checks and in asserting the rule of law for all to protect minority interests. Most recently, much attention has been devoted to the resurgence of populist politics in the West and the erosion of these inherited institutional and normative checks. This latest populist turn is also highly consequential for the Asian region and threatens one of its dominant characteristics − complex interdependence.

Political Populism and Disruption in Asia

Most obviously, political populism is typically associated with a nativist turn away from economic openness and the growing trade, investment and financial interdependence on which the Asian region collectively has relied as drivers of growth and prosperity. A second, related reason is that political populism has also been associated with a growing distrust of multilateral diplomacy and international institutions generally, as well as a tendency to defend narrower conceptions of national interest.

The Asian region exhibits highly complex forms of interdependence, but by comparison with the North Atlantic region and Western Europe in particular, these interdependencies are relatively loose and less deeply institutionalised. This has often been seen as having advantages of flexibility and efficiency, but as political populism reshapes the global order it may make Asia’s regional order more vulnerable to disruption.

The Trump administration’s sudden withdrawal from Syria and the current UK government’s last-ditch tactics in the ongoing Brexit negotiations are both symbolic of this shift as well as systemically consequential. Populist leaders are unlikely to coordinate in a new “populist internationale”, but the policy reorientation of the two powers most associated with the post-1945 “liberal order” has wider implications.

Turkey’s decision to invade northern Syria and the deterioration of Japan-South Korea relations are plausible examples. Both suggest that governments in longstanding US allies feel increasingly emboldened to depart from international behavioural norms in security and foreign policy. The US itself has long had a tendency to justify a mix of multilateralism with unilateral national measures, but the Trump administration’s much sharper emphasis on the latter alters the calculations of many other governments.

Varieties of Political Populism in Asia

A third reason why political populism is consequential for Asia is that it is taking hold in important countries in the region, albeit in highly varied forms. Figure 1 illustrates the average vote share of populist parties by region in legislative elections since 20001. It shows that conceived broadly, populism in Asia has been nearly as successful as in Europe since the turn of the century.

This figure underestimates its importance in Asia, since the vote share of populist candidates in presidential elections is typically much higher (likely reflecting a tendency for populist parties to be dominated by charismatic leaders). For Asia since 2000, populist presidential candidates obtained an average vote share of 28%, with a rising trend over time.

Taking both legislative and presidential elections into account, the data indicate that political populism has been especially important in Indonesia, India, the Philippines, South Korea and Taiwan.

We are aware that characterisations of particular cases are often contested by specialists. Yet our dataset is unique in distinguishing different varieties of populism, identifying the primary “out-group(s)” that populist leaders and parties seek to target as enemies of the people.

Compared to Europe, Latin America and Oceania, Asian populism is rarely strongly anti-immigrant. More often, it targets domestic political elites (in legislative elections generally and in presidential elections in the Philippines), domestic ethnic groups (in Bangladesh, India and Taiwan) or foreign threats (in Pakistan, South Korea and especially Taiwan).

_______________________

1 The data are drawn from a populism coding project initiated by the University of Melbourne and including collaborators at the University of Cambridge, the LSE and RMIT (Melbourne). The dataset adopts an inclusive definition of populism, using a mixture of party manifestos, leader speeches, expert opinion and scholarly literature to identify candidates and parties that seek to mobilise political support based on a rhetorical dualism between the “people” and “elites” or other out-groups.

Figure 1: Average aggregated vote share for populist parties by major region in legislative elections, 2000-2019

Source: Global populism dataset, University of Cambridge/LSE/RMIT/University of Melbourne.

Political Populism and Political Nationalism

Regarding the latter, distinguishing political populism from more traditional forms of political nationalism can be particularly challenging. Clearly, some mainstream political parties also seek to deploy nationalism as a vote mobiliser (though it is not their dominant characteristic). This is conspicuously true for the ruling Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, which may be an important reason why populist parties there have been less successful than elsewhere.

The South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s centrist-liberal Democratic Party has also reflected and tactically deployed the considerable popular nationalist sentiment in South Korean society as he vowed in early August that in the escalating bilateral trade dispute the country would “never again lose to Japan”. More charitably, the demonstrated ability of populist parties in South Korea to tap into deep-seated nationalist sentiment may mean that mainstream parties find it difficult to avoid doing the same.

A similar phenomenon can be observed in the UK’s Conservative Party since 2016, where the success of populist movements and the associated UKIP and Brexit parties has driven the party towards an uncompromising “hard Brexit” position. Both developments underline the growing fragility of multilateralism in Europe and Asia and of the complex interdependence that it generated.

About the Author

Andrew Walter is NTUC Professor of International Economic Relations, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore and Professor of International Relations in the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Melbourne. His previous academic positions were at Oxford University and the London School of Economics and Political Science.