26 December 2025

- RSIS

- Publication

- RSIS Publications

- Towards a “We-First” Society in Singapore

SYNOPSIS

Although Singaporeans exhibit high levels of generosity, there appears to be a weaker sense of civic-mindedness, revealing a paradox between generosity of giving and underlying attitudes toward taking responsibility for others. While the government shapes much of civic life in Singapore, institutionalised and incentivised giving may unintentionally “crowd out” civic-mindedness. What the city-state now needs is to cultivate a “crowd in” mindset by deepening the meaning of giving so that a “We-First” society is not just a vision but a lived reality.

COMMENTARY

In his first National Day Rally speech, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong highlighted the importance of cultivating a “We-First” society, where individuals look beyond their own self-interest to care for the wider community. In his view, investing in social capital and strengthening bonds within society is crucial for navigating future challenges, just as the Singapore Spirit carried the nation through the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the 2024 World Giving Index (WGI), Singapore ranks third globally in giving behaviour, behind Indonesia (1st) and ahead of regional peers such as Thailand (14th) and Malaysia (20th). Based on data from the National Giving Study (NGS), volunteering rates rose from 22 per cent in 2021 to 30 per cent in 2023, while donation rates remained stable at 62 per cent.

Despite these positive trends in giving and the government’s emphasis on strengthening social cohesion, questions remain about how Singaporeans will translate the “We-First” vision into everyday civic action. For instance, while volunteering rates had risen, the National Giving Study also found a decline in the number of hours volunteered and the amount of donations to charity, suggesting time and financial constraints as possible reasons.

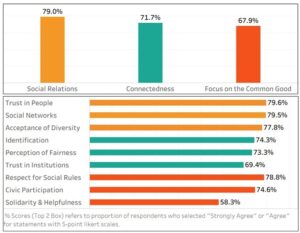

Besides practical barriers to giving, the Southeast Asian Social Cohesion Radar – a 2025 study assessing social cohesion across ten ASEAN states – found that civic-mindedness is relatively weaker. As shown in Figure 1, “Focus on the Common Good” scored the lowest at 67.9 per cent – a sub-domain measuring perceptions and behaviours reflecting responsibility for others – compared to “Social Relations” (79.0 per cent), which measures the quality of sectarian relations, and “Connectedness” (71.7 per cent), which assesses the degree of public confidence and trust in the state.

Figure 1: Scores on Social Cohesion Domains and Dimensions for Singapore

Upon closer examination of the “Solidarity and Helpfulness” dimension, support and care for others are rated significantly lower than in other dimensions. For instance, one in two agreed that Singaporeans think it is important to do community work (48.9 per cent) or to donate to the poor (52.5 per cent). To realise the “We-First” society, it is crucial to nurture an intrinsic sense of responsibility.

Crowding Out of Responsibility? – Disproportionate Roles Between Government and Civil Society

What explains the lacklustre culture of giving among Singaporeans in general? One possible explanation lies in the disproportionate roles between the government and civil society in organising and institutionalising giving. While the “Many Helping Hands” (MHH) approach – adopted as government policy to support vulnerable communities – was intended to involve a broad network of actors, such as Voluntary Welfare Organisations (VWOs), donors, funders and volunteers, its implementation in practice may continue to skew heavily toward the government.

The government’s strong role enables efficient coordination and delivery of policies at the national level, ensuring that vulnerable communities are cared for. But this dominance may also cultivate a reliance on the state as reflected in public expectations of who should provide help. For example, a survey on who should provide basic needs found that 63.7 per cent of respondents chose the government, higher than those who selected the community (59.3 per cent) or themselves (41.3 per cent), indicating that the government is widely seen as the primary provider for basic necessities.

Furthermore, the inclination toward government-led solutions reduces opportunities and perceived responsibility for contributing to meet wider societal challenges. This dynamic aligns with the “Crowding Out Hypothesis” discussed in the context of welfare states and social spending across European countries. The hypothesis suggests that when formal state mechanisms expand through initiatives and programmes aimed at uplifting vulnerable groups, they can inadvertently reduce social capital by reducing the citizens’ direct involvement, displacing informal care networks, and thereby lowering civic commitment.

While Singapore’s context differs from that of European welfare states, the government’s substantial role in service delivery, coupled with public perceptions that it should take the lead, reinforces this reliance and limits opportunities for self-organisation. This is reflected in the various levers that institutionalise giving across different stages of life.

From a young age, Singaporeans participate in mandatory school-based volunteering – previously known as Community Involvement Programme (CIP), now known as Values-In-Action (VIA) Programme – as part of the national education framework. Similarly, at the workplace, contributions to ethnic self-help groups are automatically deducted from monthly wages through the Central Provident Fund (CPF) Board, ensuring consistent contributions to society across ethnic lines, but this reduces the voluntary aspect of giving back to society.

As such, giving back to society in Singapore tends to be institutionalised and structured, rather than voluntary. While these measures ensure consistency and encourage broad-based contributions, they leave limited room for citizens to develop a sense of commitment to others in society and reduce opportunities to hone skills in self-organising for the common good. In other words, the dominance of and reliance on government-led provisions over civic initiatives continues to crowd out the citizens’ sense of responsibility, thereby dampening the emergence of bottom-up efforts essential to cultivating genuine civic-mindedness.

Crowding out Motivations? – The Role of Incentives in Giving

Another possible explanation for Singaporeans’ attitude toward giving may lie in the role of rewards and incentives in shaping giving behaviour. Such rewards and incentives can encourage participation, but they do so by motivating behaviour through extrinsic inducements rather than intrinsic motivations, such as the sense of fulfilment. This displacement of intrinsic motivation, known as the “Motivation Crowding Effect”, suggests that external rewards, such as monetary incentives, can undermine genuine altruism.

In Singapore, government-led initiatives that incentivise giving may have inadvertently contributed to this dynamic. The World Giving Index (WGI) noted Singapore’s 19-place rise, attributing it partly to policies that incentivise giving. For instance, at the workplace, the Corporate Volunteer Scheme, enhanced in 2024, allows companies to claim a 250 per cent tax deduction on qualifying expenditure when employees volunteer with registered charities. Individuals likewise enjoy a 250 per cent tax deduction for donations to approved charities, which means a $1 donation reduces taxable income by $2.50.

Despite these incentives, online discussions on volunteering reveal a broader range of motivations driving volunteerism among Singaporeans. Figure 2 presents selected excerpts from a social media scan on volunteerism conducted by the Social Cohesion Research Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. Some cited personal fulfilment, enjoyment and community service (intrinsic drivers), while others cited instrumental reasons such as job search, socialising or meeting like-minded partners (extrinsic drivers). Taken together, these conversations highlight the multifaceted motivations for volunteering and giving, including both intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

Figure 2: Screenshots of Online Discussions on Volunteering

Nonetheless, as the National Giving Study highlights, intrinsic motivations sustain volunteering and giving behaviour over time, whereas extrinsic motivations are more short-lived. As such, nurturing intrinsic motivations – rooted in values of care and shared responsibility for the common good – will be key in deepening the culture of care needed to realise a civic-minded “We-First” society, where motivations and behaviours align.

Crowding In Civic Spirit? – Towards a “We-First” Society

The key question, then, is how we can “crowd in”, i.e., cultivate, a sense of intrinsic civic spirit in Singapore, where, hitherto, civic life is largely shaped by the government? While the goal is to nurture intrinsic motivation, a practical first step – to build momentum – could be to tap into existing structures that institutionalise and incentivise giving. By using the government’s strong enabling role as a scaffold, rather than a substitute for citizen action, non-monetary rewards can be introduced to encourage volunteering. Over time, this can evolve into self-driven civic acts as individuals begin to see volunteering as part of their identity.

Timebanking exemplifies this approach. It works by using time as a form of currency, where each hour of volunteer work earns a credit that can be exchanged for services offered by other individuals or organisations. Unlike traditional volunteering, it encourages reciprocity, provides non-monetary recognition, and gives participants autonomy to choose the type of support they would like to receive in return.

In Hong Kong, timebanking has been used to encourage volunteering among older adults. While some question whether timebanking may crowd out altruistic motives, a recent study found the opposite: participants increased their volunteering hours within timebanking programmes and viewed credits as symbolic recognition rather than payment. Importantly, as the study noted, generativity – a concern and commitment to future generations – remained the central motivation for volunteering among older adults.

In Singapore, government-backed platforms like KampungSpirit and giving.sg make volunteering and donations accessible and transparent. A timebanking model or a points system based on hours volunteered could complement these efforts by making civic participation more visible and rewarding, similar to how the Healthy 365 App promotes healthy living through gamified tracking. Such a recognition system can turn reward-based participation into sustained engagement, as volunteering becomes a regular habit and an integral part of one’s identity, ultimately fostering intrinsic motivation and helping sustain participation in the long run.

Beyond digital systems, other factors such as religion, education, the arts, culture, and sports also play nurturing roles by giving meaning to acts of personal contribution. While timebanking helps establish habits of giving through repeated participation, these factors offer reflection on why helping matters – through shared narratives, collective goals, and experiences of belonging, such as teamwork in sports, service in faith communities, or collective creation in the arts. In doing so, they translate routine civic action into intrinsically motivated commitment and reinforce the sinews of a “We-First” society.

About the Authors

Lam Teng Si is a Senior Analyst at the Social Cohesion Research Programme at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. Syahirah Sasman is a postgraduate student in International Relations at RSIS.

SYNOPSIS

Although Singaporeans exhibit high levels of generosity, there appears to be a weaker sense of civic-mindedness, revealing a paradox between generosity of giving and underlying attitudes toward taking responsibility for others. While the government shapes much of civic life in Singapore, institutionalised and incentivised giving may unintentionally “crowd out” civic-mindedness. What the city-state now needs is to cultivate a “crowd in” mindset by deepening the meaning of giving so that a “We-First” society is not just a vision but a lived reality.

COMMENTARY

In his first National Day Rally speech, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong highlighted the importance of cultivating a “We-First” society, where individuals look beyond their own self-interest to care for the wider community. In his view, investing in social capital and strengthening bonds within society is crucial for navigating future challenges, just as the Singapore Spirit carried the nation through the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the 2024 World Giving Index (WGI), Singapore ranks third globally in giving behaviour, behind Indonesia (1st) and ahead of regional peers such as Thailand (14th) and Malaysia (20th). Based on data from the National Giving Study (NGS), volunteering rates rose from 22 per cent in 2021 to 30 per cent in 2023, while donation rates remained stable at 62 per cent.

Despite these positive trends in giving and the government’s emphasis on strengthening social cohesion, questions remain about how Singaporeans will translate the “We-First” vision into everyday civic action. For instance, while volunteering rates had risen, the National Giving Study also found a decline in the number of hours volunteered and the amount of donations to charity, suggesting time and financial constraints as possible reasons.

Besides practical barriers to giving, the Southeast Asian Social Cohesion Radar – a 2025 study assessing social cohesion across ten ASEAN states – found that civic-mindedness is relatively weaker. As shown in Figure 1, “Focus on the Common Good” scored the lowest at 67.9 per cent – a sub-domain measuring perceptions and behaviours reflecting responsibility for others – compared to “Social Relations” (79.0 per cent), which measures the quality of sectarian relations, and “Connectedness” (71.7 per cent), which assesses the degree of public confidence and trust in the state.

Figure 1: Scores on Social Cohesion Domains and Dimensions for Singapore

Upon closer examination of the “Solidarity and Helpfulness” dimension, support and care for others are rated significantly lower than in other dimensions. For instance, one in two agreed that Singaporeans think it is important to do community work (48.9 per cent) or to donate to the poor (52.5 per cent). To realise the “We-First” society, it is crucial to nurture an intrinsic sense of responsibility.

Crowding Out of Responsibility? – Disproportionate Roles Between Government and Civil Society

What explains the lacklustre culture of giving among Singaporeans in general? One possible explanation lies in the disproportionate roles between the government and civil society in organising and institutionalising giving. While the “Many Helping Hands” (MHH) approach – adopted as government policy to support vulnerable communities – was intended to involve a broad network of actors, such as Voluntary Welfare Organisations (VWOs), donors, funders and volunteers, its implementation in practice may continue to skew heavily toward the government.

The government’s strong role enables efficient coordination and delivery of policies at the national level, ensuring that vulnerable communities are cared for. But this dominance may also cultivate a reliance on the state as reflected in public expectations of who should provide help. For example, a survey on who should provide basic needs found that 63.7 per cent of respondents chose the government, higher than those who selected the community (59.3 per cent) or themselves (41.3 per cent), indicating that the government is widely seen as the primary provider for basic necessities.

Furthermore, the inclination toward government-led solutions reduces opportunities and perceived responsibility for contributing to meet wider societal challenges. This dynamic aligns with the “Crowding Out Hypothesis” discussed in the context of welfare states and social spending across European countries. The hypothesis suggests that when formal state mechanisms expand through initiatives and programmes aimed at uplifting vulnerable groups, they can inadvertently reduce social capital by reducing the citizens’ direct involvement, displacing informal care networks, and thereby lowering civic commitment.

While Singapore’s context differs from that of European welfare states, the government’s substantial role in service delivery, coupled with public perceptions that it should take the lead, reinforces this reliance and limits opportunities for self-organisation. This is reflected in the various levers that institutionalise giving across different stages of life.

From a young age, Singaporeans participate in mandatory school-based volunteering – previously known as Community Involvement Programme (CIP), now known as Values-In-Action (VIA) Programme – as part of the national education framework. Similarly, at the workplace, contributions to ethnic self-help groups are automatically deducted from monthly wages through the Central Provident Fund (CPF) Board, ensuring consistent contributions to society across ethnic lines, but this reduces the voluntary aspect of giving back to society.

As such, giving back to society in Singapore tends to be institutionalised and structured, rather than voluntary. While these measures ensure consistency and encourage broad-based contributions, they leave limited room for citizens to develop a sense of commitment to others in society and reduce opportunities to hone skills in self-organising for the common good. In other words, the dominance of and reliance on government-led provisions over civic initiatives continues to crowd out the citizens’ sense of responsibility, thereby dampening the emergence of bottom-up efforts essential to cultivating genuine civic-mindedness.

Crowding out Motivations? – The Role of Incentives in Giving

Another possible explanation for Singaporeans’ attitude toward giving may lie in the role of rewards and incentives in shaping giving behaviour. Such rewards and incentives can encourage participation, but they do so by motivating behaviour through extrinsic inducements rather than intrinsic motivations, such as the sense of fulfilment. This displacement of intrinsic motivation, known as the “Motivation Crowding Effect”, suggests that external rewards, such as monetary incentives, can undermine genuine altruism.

In Singapore, government-led initiatives that incentivise giving may have inadvertently contributed to this dynamic. The World Giving Index (WGI) noted Singapore’s 19-place rise, attributing it partly to policies that incentivise giving. For instance, at the workplace, the Corporate Volunteer Scheme, enhanced in 2024, allows companies to claim a 250 per cent tax deduction on qualifying expenditure when employees volunteer with registered charities. Individuals likewise enjoy a 250 per cent tax deduction for donations to approved charities, which means a $1 donation reduces taxable income by $2.50.

Despite these incentives, online discussions on volunteering reveal a broader range of motivations driving volunteerism among Singaporeans. Figure 2 presents selected excerpts from a social media scan on volunteerism conducted by the Social Cohesion Research Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. Some cited personal fulfilment, enjoyment and community service (intrinsic drivers), while others cited instrumental reasons such as job search, socialising or meeting like-minded partners (extrinsic drivers). Taken together, these conversations highlight the multifaceted motivations for volunteering and giving, including both intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

Figure 2: Screenshots of Online Discussions on Volunteering

Nonetheless, as the National Giving Study highlights, intrinsic motivations sustain volunteering and giving behaviour over time, whereas extrinsic motivations are more short-lived. As such, nurturing intrinsic motivations – rooted in values of care and shared responsibility for the common good – will be key in deepening the culture of care needed to realise a civic-minded “We-First” society, where motivations and behaviours align.

Crowding In Civic Spirit? – Towards a “We-First” Society

The key question, then, is how we can “crowd in”, i.e., cultivate, a sense of intrinsic civic spirit in Singapore, where, hitherto, civic life is largely shaped by the government? While the goal is to nurture intrinsic motivation, a practical first step – to build momentum – could be to tap into existing structures that institutionalise and incentivise giving. By using the government’s strong enabling role as a scaffold, rather than a substitute for citizen action, non-monetary rewards can be introduced to encourage volunteering. Over time, this can evolve into self-driven civic acts as individuals begin to see volunteering as part of their identity.

Timebanking exemplifies this approach. It works by using time as a form of currency, where each hour of volunteer work earns a credit that can be exchanged for services offered by other individuals or organisations. Unlike traditional volunteering, it encourages reciprocity, provides non-monetary recognition, and gives participants autonomy to choose the type of support they would like to receive in return.

In Hong Kong, timebanking has been used to encourage volunteering among older adults. While some question whether timebanking may crowd out altruistic motives, a recent study found the opposite: participants increased their volunteering hours within timebanking programmes and viewed credits as symbolic recognition rather than payment. Importantly, as the study noted, generativity – a concern and commitment to future generations – remained the central motivation for volunteering among older adults.

In Singapore, government-backed platforms like KampungSpirit and giving.sg make volunteering and donations accessible and transparent. A timebanking model or a points system based on hours volunteered could complement these efforts by making civic participation more visible and rewarding, similar to how the Healthy 365 App promotes healthy living through gamified tracking. Such a recognition system can turn reward-based participation into sustained engagement, as volunteering becomes a regular habit and an integral part of one’s identity, ultimately fostering intrinsic motivation and helping sustain participation in the long run.

Beyond digital systems, other factors such as religion, education, the arts, culture, and sports also play nurturing roles by giving meaning to acts of personal contribution. While timebanking helps establish habits of giving through repeated participation, these factors offer reflection on why helping matters – through shared narratives, collective goals, and experiences of belonging, such as teamwork in sports, service in faith communities, or collective creation in the arts. In doing so, they translate routine civic action into intrinsically motivated commitment and reinforce the sinews of a “We-First” society.

About the Authors

Lam Teng Si is a Senior Analyst at the Social Cohesion Research Programme at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. Syahirah Sasman is a postgraduate student in International Relations at RSIS.