Key Trends in Digital Extremism 2025: Glocalisation, Decentralisation, and Ideological Hybridisation in Southeast Asia

In 2025, the digital extremist ecosystem consolidated rather than evolved, entrenching trends of decentralisation, localisation and hybridisation across ideological lines. The Islamic State (IS) terrorist group refocused on geopolitical crises, amplifying African operations through Al-Amaq and moral obligation narratives via Fursan al-Tarjuma, while Al-Qaeda (AQ) re-emerged with Sadaa al-Thughur (Echo of the Frontiers) to reassert relevance around Gaza. In Southeast Asia, pro-IS and pro-Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) networks adapted global events to local grievances, exploiting unrest and cultivating niche subcultures, such as jihadist nasheeds and do-it-yourself (DIY) weapons circles. Parallel far-right ecosystems glocalised Western narratives into local identity struggles, underscoring an increasingly diffused, post-organisational and cross-ideological online threat environment.

Introduction

In 2025, the digital landscape of extremism has been defined by the consolidation and deepening of trends previously observed. The persistence of these previously highlighted trends[1] has contributed to the ongoing resilience of extremist and terrorist movements, despite fewer attacks.[2] Islamist extremist and far-right actors alike have continued to strengthen their reliance on decentralised supporter networks and localised online content-sharing ecosystems, which allow them to sustain online activity despite intensified moderation efforts.

These online networks and ecosystems have in turn proliferated as they increasingly become key vehicles for threat actors to carry out their radicalisation and community-building efforts. Platform migration remains an enduring feature of this ecosystem, with actors continuing to explore lesser-known or decentralised platforms, while maintaining footholds on mainstream social media. The steady escalation of these threats has also been exacerbated by innovations in the use of artificial intelligence (AI),[3] immersive simulations such as virtual and augmented reality,[4] and the continued presence of non-mainstream subcultures[5] within the digital landscape.

In terms of online propaganda and discourse, geopolitical developments in the Middle East – such as the conflicts in Gaza and Syria as well as escalating tensions regarding Iran – remain central narrative anchors. Far-right ecosystems have increasingly localised global narratives and symbology – a process scholars term glocalisation[6] – while hybrid “post-organisational” or “salad bar” forms of extremism blur ideological boundaries.

Official Islamic State (IS) Online Activity

In 2025, the Islamic State (IS)’s propaganda has undergone a discernible rhetorical shift, with its official media apparatus increasingly foregrounding geopolitical developments rather than theological justifications.[7] This has allowed the group to push its ideological agenda within a polarised digital landscape that is increasingly focused on such geopolitical developments – the shift thus indicates that IS’s media strategy continues to adapt based on a real-time understanding of the landscape and its wider trends.

Editorials and video releases have concentrated on discrediting the new government in Syria,[8] the conflict in Gaza and the widening Iran-Israel conflict.[9] The latter has risen as a particular focus in 2025, with official narratives framing both Iran and Israel as corrupt adversaries – Israel as an archetypal adversary of Islam and Iran as a false champion of the Palestinian cause. This allows IS to appeal to both Sunni sectarian sentiments and audiences frustrated with perceived political hypocrisy across the Middle East.[10]

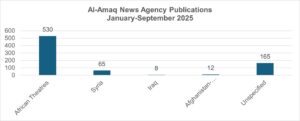

The Al-Amaq News Agency continues to function as IS’s primary news reporting arm and indicator of its operational geography. Referring to the data shown in Figure 1, the agency produced 780 publications in 2025, largely short news bulletins highlighting operational successes.[11] The majority of these video and bulletin outputs have been concentrated in Africa, numbering 530 out of 780 reports – approximately 68 percent. Operations in Nigeria were the most mentioned, numbering 188, highlighting the centrality of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) in IS’s global propaganda architecture. Mozambique and Central Africa remained consistent second-tier hubs of visibility, reflecting IS’s portrayal of the continent as a multi-jihadist theatre. Furthermore, all 42 photo reports published were linked to operations in African theatres, with none of them referencing Syria, Iraq or Khorasan. Meanwhile, the second highest region mentioned in reports was Syria, numbering 65 out of 780, or approximately 8 percent. This suggests that IS continues to use its operations in its African provinces to demonstrate its vitality and ongoing activity,[12] as a counterpart to its editorial works which leverage global events to maintain ideological continuity.

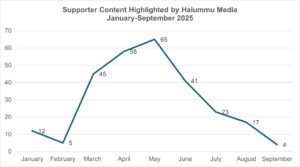

Meanwhile, Fursan al-Tarjuma, the officially recognised umbrella collective of major IS supporter (ansar) media organisations, has retained its pivotal role in the dissemination and translation of central IS propaganda. Aside from its translation of central IS propaganda, which as of 2025 spans an estimated 17 languages across 13 organisations,[13] the collective’s choices in what supporter-created posters and videos to translate and disseminate also provide insight into IS’s evolving priorities. As seen in Figure 2, data from Halummu Media – the key English translation outlet under Fursan al-Tarjuma – indicates that the frequency at which the group translates and disseminates supporter material ebbs and flows over the year, seemingly in relation to major geopolitical developments. The peak of publications in May was likely linked to coverage of and narrative over the Iran-Israel war, while the following decline coincided with both the Ramadan period as well as a lull in major developments – an indication of ongoing difficulties in sustaining a regular output, likely due to the efforts required to source and translate such materials.

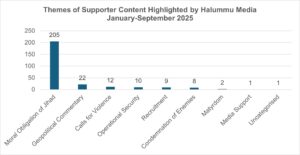

As shown in Figure 3, the themes of supporter content chosen by Halummu Media have largely emphasised the moral obligation of jihad (205 out of 270 publications), with geopolitical commentary (22 out of 270), calls for violence and lone-actor attacks (12 out of 270), and operational security (10 out of 270) as other key themes. Notably, the calls for violence were largely aimed at audiences outside active IS conflict zones, indicating IS’s continued interest in exhorting lone actors to conduct attacks, particularly in the West. It is important to note that this data simply indicates the priorities of one organisation in the collective, which may differ depending on the translation outlet analysed. Nevertheless, this framing underscores the decentralised yet interlinked nature of IS’s global propaganda ecosystem, where semi-autonomous supporter groups function as amplifiers of the organisation’s ideological core.

With regard to the online infrastructure behind this dissemination, the takedown of IS’s primary archival websites Al-Raud and I’lam in mid-2024[14] has continued to result in a vacuum within the group’s online architecture – a gap that by late 2024 had already begun to be filled by decentralised actors on less well-known platforms.[15] By early 2025, this void had been filled through the emergence of new archival and distribution platforms, notably Al-Fustat – a dark web repository mirroring official IS media output – and Saha Wagha, a smaller surface web and dark web hybrid site circulating al-Naba newsletters and audio speeches from IS leaders.[16] Both platforms restrict themselves to official IS materials, reflecting an attempt to preserve the authenticity and continuity of central messaging while distancing themselves from unofficial supporter productions. Parallel to these replacements, the TechHaven platform has become the primary hub for IS-aligned media groups, hosting a proliferation of micro-collectives such as Bengal Media, Al-Isabah Foundation, Al-Saif Media and Al-Asad Foundation.[17]

Another notable development in 2025 has been IS’s gradual integration of AI into its media strategy. Analyses by the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) have identified increasingly refined generative AI (GenAI)-produced visuals across IS-affiliated publications, with machine learning tools now used to produce posters, enhance imagery and generate multilingual translations.[18] These tools have resulted in lowered production barriers for IS and its supporters, enabling smaller teams to replicate the professional visual quality once limited to central media units. At the same time, such automation introduces a conflict between visibility and security: while GenAI allows IS to increase publishing frequency and evade detection, it also heightens the risk of forensic tracing through model-specific artefacts, pushing IS propagandists to experiment with stylometric obfuscation (modifying text to hide author identities) and encrypted workflows.[19]

Official Al-Qaeda (AQ) Online Activity

In 2025, Al-Qaeda (AQ)’s propaganda was defined by the launch of its new Arabic-language newsletter, Sadaa al-Thughur (Echo of the Frontiers), produced by the Global Islamic Media Front (GIMF).[20] The publication’s emergence in June 2025 marks AQ’s most significant media initiative in recent years and signals a renewed effort to consolidate its global messaging under a unified digital front. Distributed through pro-AQ Rocket.Chat and Telegram channels, Sadaa al-Thughur functions as both an ideological anchor and an attempt to re-centralise communication across AQ’s dispersed regional media entities, including Al-Kata’ib (Al-Shabaab), Al-Andalus (Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM) and Al-Zallaqa (Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimeen, or JNIM).[21]

Stylistically, Sadaa al-Thughur mirrors the format of IS’s al-Naba, featuring editorials, leadership messages and illustrated battle reports accompanied by infographics. This copycat approach underscores AQ’s pragmatic adaptation within the jihadist media ecosystem – replicating IS’s proven outreach model while retaining AQ’s distinct ideological tone.[22] The newsletter’s early issues articulate four consistent objectives: 1) mobilising support for armed jihad; 2) defending the legitimacy of the mujahideen; 3) countering “Western misinformation”; and 4) reframing media activism as an act of worship.

Content contributions from senior figures, such as Ibrahim al-Qosi (Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, or AQAP), Abu Yasir al-Jazairi (AQIM) and Ali Mahmoud Raji (Al-Shabaab), illustrate coordinated narrative alignment across global and regional fronts.[23] Their writings converge on a shared grievance – Palestine, particularly Gaza – used as a rallying symbol to link struggles in Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. Collectively, Sadaa al-Thughur demonstrates AQ’s attempt to reassert narrative coherence and elevate its moral authority – likely in competition with IS media efforts – by similarly fusing global threat discourse with regionally grounded legitimacy.

Extremist Islamist Activity Online in Southeast Asia

Supporter groups have emerged at the forefront of propaganda operations in Southeast Asia in recent years.[24] This decentralised network of unofficial groups recontextualises extremist ideologies to suit domestic audiences by translating core propaganda and exploiting local and international grievances. Pro-IS supporters in particular have built niche online communities through shared interests such as jihadist nasheeds, circulation of do-it-yourself (DIY) weapons-making manuals and various cultural touchpoints.

Pro-IS, Pro-AQ and Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia (HTI)’s Responses to Global Trends

Regional supporter groups mirror global trends, republishing core propaganda in local languages and exploiting political crises to reinforce radical master narratives. The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024 marked a critical inflection point for pro-IS, pro-AQ and pro-Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) supporters within the region, as sympathisers across all three entities capitalised on Syria’s uncertain political transition to promote their core group’s ideologies and discredit rival narratives.[25] Indonesian pro-AQ supporters amplified positive framings of HTS, portraying Syria’s regime transition as divinely ordained. Former Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) member Mas’ud Izzul Mujahid amplified this view via his outlet Andalus, long known for promoting violent sectarian narratives.[26]

Conversely, pro-IS channels branded HTS as anti-Islam and Ahmed al-Sharaa as an apostate for engaging Western officials,[27] while Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) pages condemned the new regime for failing to declare a caliphate and disparaged the new Syrian leader al-Sharaa as a traitor to tawhid (the oneness of God).[28] These online narratives demonstrate how Indonesian extremist actors have exploited the Syrian transition to reinforce ideological divisions and legitimise their own doctrinal positions.

Indonesian Protests

Nationwide protests in Indonesia in August 2025 over economic grievances escalated after a viral video of the police killing a delivery rider, leaving at least 10 people dead.[29] Both HTI and pro-IS supporters leveraged the opportunity to promote their extremist narratives and embed their messaging within wider public discourse.

Pro-IS Supporters

Indonesian pro-IS supporters online capitalised on domestic instability and public socio-political grievances during the Indonesian protests to justify violence and mobilise against the kafir (infidel) government. Online supporters, particularly on Facebook, worked to frame the police as merely pawns of the taghut (tyrannical) government, peddling the narrative that social unrest and state-inflicted injustice are inevitable byproducts of kafir democratic rule.[30] Pro-IS supporters incited acts of terror and violence by sharing videos of police officers being subjected to physical attacks, accompanied by claims that the blood of “anshar taghut” (supporters of tyrants) is halal (permissible), in addition to exploiting scriptural verses to justify waging war against musyrikin (polytheists).[31]

HTI

HTI channels used the unrest to call for the dismantling of democracy, framing it as proof that only an Islamic caliphate can end corruption and tyranny. One key HTI propaganda outlet propagated the narrative that the only “correct path” to alleviate suffering and address the root problems of society is by establishing the khilafah (caliphate) and implementing Islamic shariah law. Pertinently, the platform called for Muslims to “abandon the corrupt system of democracy” and “fight to establish an Islamic state”, eventually culminating in the “full establishment of Islam across the world”.[32]

Significantly, HTI-linked accounts delineated a practical method for how the organisation envisions the democratic system to be toppled and for the khilafah to be established through a three-step plan, comprising education and training, socialisation and elite buy-in, and the eventual transfer of power.[33] While the mechanics of the establishment of the khilafah are typically excluded from propaganda-centric posts, this development points to the likelihood that HTI saw this period of domestic volatility as a serious disruption to the status quo of Indonesian politics and society, and viewed this as an important opportunity for the party to signal its readiness to fill a potential power vacuum that may emerge.

Key HTI Developments

International Union of Muslim Scholars (IUMS) Fatwa

On March 28, 2025, the International Union of Muslim Scholars (IUMS) issued a fatwa, or legal opinion, concerning the Israel-Hamas war and the transgression of an earlier ceasefire that had been brokered.[34] The fatwa outlined several key rulings, including the obligation of armed jihad against the occupation in Palestine for every able-bodied Muslim in the Islamic world. In response to the ruling, Indonesia’s foremost organisation of Islamic scholars, Majelis Ulama Indonesia (MUI), published an online press release in April 2025 conveying its “full support” for the decree, noting it is “obligatory for Muslims to defend Palestine”.[35]

HTI supporters on Facebook were especially supportive of MUI’s decision to back the fatwa and leveraged the announcement as an implicit endorsement of the obligatory nature of jihad against enemy out-groups as well as the imperative need to establish the khilafah. Key HTI-affiliated accounts, which contribute to thought leadership and propaganda campaigns in service of the khilafah cause, also capitalised on MUI’s endorsement of the fatwa to amplify HTI’s ideology and exclusivist narratives. These accounts called for adherents to fulfil their religious obligation of implementing “Islamic principles in all corners of the world with [dakwah, or proselytisation] and jihad”.[36] HTI propaganda platforms also dismissed the role of diplomacy as a tool to broker peace in the region, asserting instead that jihad is the only path of recourse to overcome the crisis in Gaza.[37]

“Aksi Bela Palestina” Rally 2025

HTI organised a series of coordinated rallies in November 2024 as well as in January and February 2025, with the intent of mobilising large groups of supporters. Branded as “Aksi Bela Palestina” (Action to Defend Palestine), the demonstrations leveraged the Israel-Hamas war as a mobilising narrative to encourage Indonesians to call for the establishment of the khilafah and to legitimise jihad as the only solution to liberate Palestine.[38]

In response to a livestream of the Jakarta rally on January 26, which accrued over 100,000 views, online sympathisers expressed their overwhelming support for the demonstration.[39] These online supporters framed protesters as divinely sanctioned defenders of Islam, quoting the verse, “kill them where you find them”.[40] The effect of the rallies in emboldening HTI supporters is embodied in the Facebook post of one HTI adherent, who declared that HTI is “not banned because it has never been banned” and that the organisation is “not resurfacing because it has never been drowned out”.[41]

Diversified Community-Building Tactics in Southeast Asia

In 2025, extremist Islamist supporter groups have continued leveraging diversified tactics to cultivate sustainable extremist online communities regionally across mainstream and encrypted chat platforms.

Pro-IS Jihadist Nasheed Online Subculture

The Indonesian pro-IS online extremist ecosystem has witnessed the emergence of a nascent regional jihadist nasheed (Islamic vocal music) subculture on mainstream online platforms. On Facebook, one popular Indonesian extremist nasheed distributor has been found uploading edited videos of extremist nasheeds originally produced by IS Central and its affiliates, with translations and key calls to action in Bahasa Indonesia. These media collaterals focus on peddling explicitly violent narratives on the pretext of religious deference and obligation. The bulk of these nasheeds call for listeners who are “true believers” to engage in offensive jihad and to wage war against “enemy” out-groups in service of God and IS.[42]

Pertinently, this extremist subculture has been effective in cultivating an active and engaged radical online community. In the case of the aforementioned Indonesian nasheed distributor on Facebook, the channel administrator strategically maintains a high level of interaction with supporters, responding to their nasheed requests and accommodating their feedback. These interactions and the shared passion for nasheeds amongst supporters foster a sense of community between extremist sympathisers, exacerbating the risk of further radicalisation in terms of group expansion and potential spillover to mainstream audiences.[43]

Pro-IS DIY Explosives and Weapons Online Interest Group

In June 2025, a pro-IS channel that specialises in homemade explosives and DIY weapons making was shared in Tamkin Indonesia, the key online Indonesian pro-IS outfit under Fursan al-Tarjuma.[44] A direct link to the group was shared with Indonesian supporters, along with an image summarising the group’s repertoire of homemade explosives and capabilities. This included five key areas of expertise: 1) explosive recipes; 2) improvised explosive devices (IEDs); 3) initiation systems and detonators; 4) remote initiation systems; and 5) information security resources.

- Significantly, the group actively disseminates comprehensive instructions for the manufacture of homemade explosives, including information on precursor chemicals, equipment and jihadist preparedness manuals. These collaterals are intentionally designed to be accessible to beginners, thereby lowering the barrier to entry for violent extremist activity. The group also frequently employs the strategic use of outlinking, where it redirects users to external channels where more specific or technical queries can be posed directly. This enables the tailoring of explosives-making advice to individual use cases. Outlinking may also contribute to the cultivation of tightly knit sub-groups that are less subject to security surveillance.

Shifting Dynamics in Far-Right Extremism: Glocalisation and the Rise of Post-Organisational Networks

The trajectory of far-right extremism[45] (FRE) in 2025 was shaped by two distinct yet intersecting currents that reflect its gradual shift towards an increasingly decentralised, digitally networked and globally diffused ecosystem. First, the past year has seen the continued glocalisation of the global far right’s ideological core – nativism, authoritarianism and populism – as these ideas circulate beyond their oft-associated Western loci and are refracted through local particularities.[46] Second, post-organisational dynamics have deepened, with extremist engagement and mobilisation continuing within established organisations, but also increasingly mediated through decentralised online networks and digital subcultures.

Glocalisation

As the global far right continues to make inroads into the socio-political mainstream, it has evolved into a transnational ecosystem of parties, grassroots movements, online communities and allied actors, through which compelling narratives of civilisational decline and the need for ethno-cultural homogenisation circulate. Yet these master frames are not adopted wholesale – they are adapted into locally resonant narratives and grievances, often reframing domestic anxieties as part of a broader struggle to defend against the perceived erosion of “traditional” values.[47] This occurs at a time when nativist populism has diffused globally, reinvigorated by United States (US) President Donald Trump’s open embrace of white Christian nationalism.[48] This has been echoed by similar movements such as Japan’s anti-immigrant, far-right party Sanseito.[49]

Beyond shared narratives, the transnational circulation of far-right symbols has also become increasingly evident. The recently assassinated right-wing political activist Charlie Kirk, for example, has been transformed into an “imported martyr”, invoked as a symbol of free speech and traditional values.[50] His death has been instrumental in advancing a potent narrative of victimhood – appropriated not only by far-right European parties but also by transnationally linked FRE groups, such as the US-based Proud Boys, to recruit, radicalise and, in some instances, incite violent mobilisation through their online channels.[51] This symbolic appropriation has extended even to non-Western contexts such as Korea, where a far-right youth movement organised a memorial march in his honour which echoed with anti-Chinese and Christian nationalist slogans.[52]

The same glocalising dynamic is also evident in online ecosystems. Scholars have observed, for instance, a growing ideological convergence between Hindu nationalism and the manosphere[53] – melding “patriarchal revivalism and grievance politics” in ways that mirror far-right online ecosystems in the West.[54]

Post-Organisational Dynamics

FRE, like other extremist threats across the ideological spectrum, increasingly exhibits post-organisational dynamics. Scholars note a continuing shift in how individuals engage with and are mobilised by extremism – from formal organisations to decentralised online networks which amplify shared grievances, cultivate collective identities and normalise hostility towards perceived out-groups.[55] While this undercurrent is not entirely new, nor does it indicate that FRE has fully transitioned into a post-organisational stage,[56] it nonetheless underscores the accelerating role of digital ecosystems in reshaping how extremist movements organise, communicate and sustain themselves.

Recent research examining Australian youths charged with far-right terrorism-related offences found that they displayed significantly higher levels of social media engagement.[57] The 2024 case of Jordan Patten, a 19 year old who plotted to assassinate a local member of parliament, illustrates this trend, with the white supremacist accelerationist network Terrorgram reportedly playing a “critical role” in his radicalisation.[58] Within these communities, his manifesto was circulated across affiliated channels and, following his failed attack, users dissected the incident and shared guidance for prospective assailants – underscoring how such online spaces function as hubs of collective learning and mobilisation in the absence of formal organisations.[59]

Notably, such decentralised online milieus often blur ideological boundaries and foster hybridised forms of extremism. In the United Kingdom, MUU (mixed, unclear and unstable)[60] referrals now form the largest Prevent category.[61] Recent incidents further exemplify these hybridised dynamics, with perpetrators drawing on both FRE and nihilistic violent subcultures[62] – as seen in the 2025 Annunciation Catholic Church[63] and Evergreen High School shootings.[64]

Southeast Asia’s Nascent Far-Right Extremist Digital Community

Perhaps counterintuitively for some, the twin dynamics of glocalisation and decentralised, networked engagement have become increasingly evident in Southeast Asia, reflected in the rise of diverse online FRE communities and subcultures, alongside several reported cases of online-driven radicalisation.

This process of glocalisation is evident in how regional FRE actors and sympathisers appropriate and adapt the narratives and aesthetics of the global far right. Their digital propaganda – often disseminated through memes and short-form audio-visual content – demonstrates how global FRE discourse serves as a key reference point yet is often reinterpreted in ways which resonate with local cultural expressions, grievances and socio-political contexts.

For instance, the “Great Replacement” theory, the cornerstone of global FRE discourse, has been recast to reflect the specific majority-minority dynamics of the region. Among regional FRE online communities, such as the Austronesian supremacists,[65] “out-groups” – including Rohingya refugees and ethnic minorities such as Chinese and Arabs – are portrayed as demographic threats who taint the purity of “indigenous” populations.[66] Such depictions of demographic siege are often coupled with calls for violence, with Western FRE slogans like “Total N***er Death” (TND) repurposed into localised variants such as “Total Rohingya Death” (TRD) or “Total Chinese Death” (TCD).[67]

Notably, this adaptive process has also manifested in documented FRE cases in the region. In Singapore, a 17 year old who self-radicalised online, drawing inspiration from far-right extremists such as Brenton Tarrant, was detained after planning attacks on local mosques, believing this would prevent what he perceived as a “Great Replacement” of the Chinese majority by Malays and Muslims.[68]

Glocalisation further extends to the symbolic realm, where regional communities substitute Western far-right iconography with culturally resonant alternatives. The Austronesian supremacist community, for example, has replaced the Sonnenrad[69] with regional sun emblems such as the Indonesian Surya Majapahit (Majapahit Sun) and the Sun of Liberty from the Philippine flag – illustrating how global FRE aesthetics are reimagined to reflect mythologies of civilisational ascendancy.[70]

The Philippine Falangist Front (PFF)[71] exemplifies how these glocalised narratives are embedded within decentralised, post-organisational ecosystems. Its digital propaganda on mainstream social media platforms taps into frustrations over the perceived failures of the Philippine state, portraying these as symptoms of systemic decay and attributing blame to perceived enemies, such as communists, Freemasons, Muslims and LGBTQ+ communities – often with violent overtones.[72] From these public platforms, the community funnels sympathisers into more insular spaces, most notably a gaming-adjacent Discord server which functions as a hub for ideological readings, “shitposting” and casual political discussions. Here, the Discord server acts as a conduit for mobilisation, with members engaging in collective gaming activities, including Roblox scenarios that recreate the 2019 Christchurch mosque shooting, alongside limited offline mobilisation through its “Activism through Action!” campaign, which encourages the public dissemination of the community’s propaganda posters.[73]

At the individual level, Singapore’s first recorded case of “salad bar” radicalisation underscores how these post-organisational environments foster hybrid and highly personalised extremist worldviews. The 14-year-old offender in question drew from far-right, far-left and incel subcultures while also expressing sympathy for IS, reflecting a convergence of ideological fragments facilitated by exposure to multiple online extremist communities.[74] Another case, which is still under investigation but may have an online dimension, recently transpired in Indonesia. On November 7, an attack involving explosives occurred during Friday prayers at a mosque at SMA N 72 Jakarta (72 Jakarta State High School) in North Jakarta, injuring at least 54 people.[75] While the authorities are still investigating the perpetrator’s motives, the toy submachine gun found on his person was reportedly inscribed with white supremacist slogans and the names of past FRE mass shooters.[76] Such markings, which attempt to emulate the modus operandi of past FRE attacks, at the very least point to exposure to and interaction with online FRE content.[77]

Outlook

FRE has become a transnational challenge, sustained by decentralised digital networks which adapt global narratives to local contexts. In Southeast Asia, these dynamics are producing diffused and hybrid threats that existing counter terrorism frameworks – still focused on hierarchical, ideology-driven organisations – may be ill-equipped to address.

Effective mitigation requires a holistic response which integrates both the online and the behavioural dimensions of the problem. Policymakers should examine how digital platforms amplify extremist content, assess the limits of current moderation and regulation, and strengthen early-stage detection of online risks. At the same time, the increasingly individualised and hybridised nature of radicalisation calls for a shift away from traditional, ideology-based interventions towards behavioural prevention strategies which address individual vulnerabilities, strengthen community resilience to extremist narratives and build long-term societal resistance to digitally enabled radicalisation.

About the Authors

Benjamin Mok is an Associate Research Fellow while Nurrisha Ismail and Saddiq Basha are Senior Research Analysts at the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), a constituent unit of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. They can be reached at [email protected], [email protected], and [email protected], respectively.

Thumbnail photo by Tianyi Ma on Unsplash

Citations

[1] Ahmad Helmi bin Mohamad Hasbi, Nurrisha Ismail and Saddiq Basha, “Key Trends in Digital Extremism 2024: The Resilience and Expansion of Jihadist and Far-Right Movements,” Counter Terrorist

Trends and Analyses 17, no. 1 (2025): 100-111.

[2] “Terrorism Is Spreading, Despite a Fall in Attacks,” Vision of Humanity, March 4, 2025, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/terrorism-is-spreading-despite-a-fall-in-attacks/.

[3] Erin Saltman and Skip Gilmour, Artificial Intelligence: Threats, Opportunities, and Policy Frameworks for Countering VNSAs (Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism and Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 2025).

[4] Imtiaz Baloch, “The Shadow War in Balochistan: ISKP Weaponises Digital Land to Gain Influence,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, August 4, 2025, https://gnet-research.org/2025/08/04/the-shadow-war-in-balochistan-iskp-weaponises-digital-land-to-gain-influence/; Clara Broekaert and Colin Clarke, “The New Orleans Attack: The Technology Behind IS-Inspired Plots,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, January 30, 2025, https://gnet-research.org/2025/01/30/the-new-orleans-attack-the-technology-behind-is-inspired-plots/.

[5] “Online Subcultures, Child Exploitation, and the Shifting Landscape of Terrorism,” Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism, October 3, 2025, https://gifct.org/2025/10/03/online-subcultures-child-exploitation-and-the-shifting-landscape-of-terrorism/.

[6] Saddiq Basha, “Glocalisation of Far-Right Extremism in Southeast Asia,” Center for the Study of Organized Hate, September 4, 2025, https://www.csohate.org/2025/09/04/far-right-extremism-in-southeast-asia/.

[7] Ahmad Saiful Rijal, ICPVTR internal report, April 2025.

[8] Ahmad Helmi bin Mohamad Hasbi, ICPVTR internal report, May and August 2025. See also Giuliano Bifolchi, “Al-Naba 495: Islamic State’s Propaganda Against al-Sharaa and the Syrian-Israeli Normalisation Tracks,” Special Eurasia, May 18, 2025, https://www.specialeurasia.com/2025/05/18/al-naba-495-al-sharaa-jihad/.

[9] Giuliano Bifolchi, “Islamic State Narratives on the Israel-Iran Conflict in Issue No. 500 of Al-Naba,” Special Eurasia, June 22, 2025, https://www.specialeurasia.com/2025/06/22/isis-israel-iran-al-naba/.

[10] Ahmad Saiful Rijal, ICPVTR internal report, June 2025.

[11] This data, as well as the data used in the other figures, is drawn from ICPVTR’s open-source intelligence (OSINT) monitoring of extremist Islamist online content from January to September 2025.

[12] Sheriff Bojang Jnr, “Defeated in the Middle East, Islamic State Is Rising Again in Africa,” The Africa Report, January 10, 2025, https://www.theafricareport.com/373293/defeated-in-middle-east-islamic-state-is-rising-again-in-africa/.

[13] Aaron Y. Zelin, “The Digital Battlefield: How Terrorists Use the Internet and Online Networks for Recruitment and Radicalization,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, March 4, 2025, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/digital-battlefield-how-terrorists-use-internet-and-online-networks-recruitment-and.

[14] “Major Takedown of Critical Online Infrastructure to Disrupt Terrorist Communications and Propaganda,” Europol, June 14, 2024, https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/major-takedown-of-critical-online-infrastructure-to-disrupt-terrorist-communications-and-propaganda.

[15] Hasbi, Ismail and Basha, “Key Trends.”

[16] Ahmad Helmi bin Mohamad Hasbi, ICPVTR internal report, January 2025.

[17] Zelin, “The Digital Battlefield.”

[18] Saltman and Gilmour, Artificial Intelligence.

[19] Meili Criezis, “AI Caliphate: The Creation of Pro-Islamic State Propaganda Using Generative AI,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, February 5, 2024, https://gnet-research.org/2024/02/05/ai-caliphate-pro-islamic-state-propaganda-and-generative-ai/.

[20] Ahmad Helmi bin Mohamad Hasbi, ICPVTR internal report, July 2025.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ahmad Helmi bin Mohamad Hasbi, ICPVTR internal report, August 2025.

[24] Ahmad Helmi bin Mohamad Hasbi and Benjamin Mok, “Digital Vacuum: The Evolution of IS Central’s Media Outreach in Southeast Asia,” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 15, no. 4 (2023): 1-8.

[25] Nurrisha Ismail Fakirra and Adlini Ilma Ghaisany Sjah, “Indonesian Extremists Divided Over Syria’s Regime Change,” East Asia Forum, June 4, 2025, https://eastasiaforum.org/2025/06/04/indonesian-extremists-divided-over-syrias-regime-change/.

[26] Nurrisha Ismail Fakirra and Adlini Ilma Ghaisany Sjah, ICPVTR internal report, December 2024.

[27] Fakirra and Sjah, “Indonesian Extremists Divided.”

[28] Ibid.

[29] Wahyudi Soeriaatmadja and Arlina Arshad, “‘Justice for Affan’: Outrage in Jakarta After Delivery Rider Killed by Police Vehicle in Protest Clash,” The Straits Times, August 29, 2025, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/justice-for-affan-outrage-in-jakarta-after-motorbike-driver-dies-in-protest-clash.

[30] Saddiq Basha and Nurrisha Ismail Fakirra, ICPVTR internal report, August 2025.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] “Fatwa of the Committee for Ijtihad and Fatwa at the International Union of Muslim Scholars Regarding ‘The Ongoing Aggression on Gaza and the Suspension of the Ceasefire’,” International Union of Muslim Scholars, April 1, 2025, https://iumsonline.org/en/ContentDetails.aspx?ID=38846#.

[35] “MUI Berikan Dukungan Terhadap Fatwa Jihad Melawan Israel IUMS,” MUI Digital, April 8, 2025, https://mui.or.id/baca/berita/mui-berikan-dukungan-terhadap-fatwa-jihad-melawan-israel-iums; “MUI Dukung Penuh Fatwa IUMS Yang Serukan Jihad Lawan Israel,” CNN Indonesia, April 8, 2025, https://www.cnnindonesia.com/internasional/20250408143225-120-1216803/mui-dukung-penuh-fatwa-iums-yang-serukan-jihad-lawan-israel.

[36] Saddiq Basha and Nurrisha Ismail Fakirra, ICPVTR internal report, April 2025.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Wahyudi Soeriaatmadja, “Banned Islamist Group HTI Rallies Across Indonesia, Raising Worries Over Potential Comeback,” The Straits Times, February 6, 2025, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/banned-islamist-group-hti-rallies-across-indonesia-raising-worries-over-potential-comeback; Annisa Febiola, “HTI’s Covert Movement Still Exists, Despite Being Banned Since 2017,” Tempo, February 6, 2025, https://www.tempo.co/hukum/gerak-terselubung-hti-masih-eksis-walau-dilarang-sejak-2017-1203443.

[39] Nurrisha Ismail Fakirra, “Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia Rallies for Its Caliphate,” RSIS Commentary, no. 126, June 9, 2025, https://rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/hizbut-tahrir-indonesia-rallies-for-its-caliphate/.

[40] Nurrisha Ismail Fakirra, ICPVTR internal report, January 2025.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Nurrisha Ismail Fakirra, ICPVTR internal report, October 2024.

[43] Thomas Seymat, “How Nasheeds Became the Soundtrack of Jihad,” Euronews, October 8, 2014, https://www.euronews.com/2014/10/08/nasheeds-the-soundtrack-of-jihad.

[44] Nurrisha Ismail Fakirra, ICPVTR internal report, June 2025.

[45] In line with Andrea L P Pirro’s conceptualisation of the “far right” as an umbrella concept, this paper uses the term far-right extremism (FRE) to denote the extremism associated with both the illiberal (radical) right and the anti-democratic (extreme) right – currents grounded in nativist and authoritarian principles but differing in their stance towards democratic participation. This framing is meant to highlight the increasingly porous boundaries and points of convergence between the two. For more, see Andrea L P Pirro, “Far Right: The Significance of an Umbrella Concept,” Nations and Nationalism 29, no. 1 (2023): 101–12, https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12860.

[46] Pravin Prakash, “Mapping the Ideological Core of Far-Right Movements Globally,” Center for the Study of Organized Hate, June 12, 2025, https://www.csohate.org/2025/06/12/mapping-global-far-right/.

[47] Pravin Prakash, “Far-Right Movements and the Existential Crisis of Modern Life,” Center for the Study of Organized Hate, July 18, 2025, https://www.csohate.org/2025/07/18/far-right-movements-modern-life-crisis/.

[48] Kumar Ramakrishna and Pravin Prakash, “The American Template and the Rise of a New Transnational Far-Right,” Center for the Study of Organized Hate, September 22, 2025, https://www.csohate.org/2025/09/22/new-transnational-far-right/.

[49] Naoto Higuchi, “Unpacking the Anti-Immigrant Rhetoric of Japan’s Rising Far-Right,” East Asia Forum, August 29, 2025, https://eastasiaforum.org/2025/08/29/unpacking-the-anti-immigrant-rhetoric-of-japans-rising-far-right/.

[50] Pawel Zerka, “The Imported Martyr: Echoes of Charlie Kirk in Europe,” European Council on Foreign Relations, October 8, 2025, https://ecfr.eu/article/the-imported-martyr-echoes-of-charlie-kirk-in-europe/.

[51] David Gilbert, “Extremist Groups Hated Charlie Kirk. They’re Using His Death to Radicalize Others,” WIRED, September 12, 2025, https://www.wired.com/story/extremists-hated-charlie-kirk-now-radicalizing-others/.

[52] Chanhee Heo, “Charlie Kirk Memorial in Seoul Shows Power of Christian Nationalism for Young Korean Activists,” Religion Dispatches, September 30, 2025, https://religiondispatches.org/charlie-kirk-memorial-in-seoul-shows-power-of-christian-nationalism-for-young-korean-activists/.

[53] The manosphere refers to a loose network of online communities which promote misogynistic, anti-feminist and patriarchal ideologies, often framing gender relations through narratives of male victimhood. For more, see Yasmine Wong, “Misogyny and Violent Extremism – A Potential National Security Issue,” RSIS Commentary, no. 139, September 23, 2024, https://rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/misogyny-and-violent-extremism-a-potential-national-security-issue/.

[54] Antara Chakraborthy, “The Digital Convergence of Hindu Nationalism and the Manosphere,” Center for the Study of Organized Hate, June 26, 2025, https://www.csohate.org/2025/06/26/hindu-nationalism-manosphere/.

[55] Milo Comerford, “From Cells to Cultures: Responding to ‘Hybridized’ Extremism Threats,” in Exploring Trends and Research in Countering and Preventing Extremism & Violent Extremism, eds. Emma Allen and Denis Suljić (Hedayah, 2023), 42-50, https://hedayah.com/app/uploads/2023/11/Exploring-trends-and-research.pdf; Emerging Extremism-Related Threats in the UK: Implications for Policy Responses (Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2025), https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/emerging-extremism-related-threats-in-the-uk-implications-for-policy-responses/.

[56] William Allchorn, “Towards a Truly Post-Organisational UK Far Right? The Usefulness of a Newly Emergent Concept,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, December 16, 2021, https://gnet-research.org/2021/12/16/towards-a-truly-post-organisational-uk-far-right-the-usefulness-of-a-newly-emergent-concept/.

[57] Michaela Rana, “The Generation of ‘Digital Natives’: How Far-Right Extremists Target Australian Youth Online for Radicalisation and Recruitment,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, October 7, 2025, https://gnet-research.org/2025/10/07/the-generation-of-digital-natives-how-far-right-extremists-target-australian-youth-online-for-radicalisation-and-recruitment/.

[58] Jake Evans, “Terrorgram Linked to Alleged Plot to Kill Labor Politician,” ABC News, June 27, 2025, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-06-27/terrorgram-linked-to-alleged-plot-to-kill-labor-politician/105469638

[59] Ibid.

[60] Institute for Strategic Dialogue, Emerging Extremism-Related Threats, 6–7.

[61] Home Affairs Committee, Combatting New Forms of Extremism: Written Evidence Submitted by Joe Whittaker (COM0030),” by Joe Whittaker (United Kingdom Parliament, 2025), https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/142732/html/.

[62] Nihilistic violent subcultures refer to loosely connected online communities and aesthetic movements which glorify violence, misanthropy and past mass attackers. For more, see “Terror Without Ideology? The Rise of Nihilistic Violence – An ISD Investigation,” Institute for Strategic Dialogue, May 8, 2025, https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/terror-without-ideology-the-rise-of-nihilistic-violence-an-isd-investigation/.

[63] “NCITE Briefing: The Annunciation Attack and Nihilistic Violent Extremism,” National Counterterrorism Innovation, Technology, and Education Center (NCITE), September 3, 2025, https://www.unomaha.edu/ncite/news/2025/08/nve-landing-page.php.

[64] “Evergreen High School Shooter’s Online Activity Reveals Fascination with Mass Shootings, White Supremacy,” Anti-Defamation League (ADL), September 12, 2025, https://www.adl.org/resources/article/evergreen-high-school-shooters-online-activity-reveals-fascination-mass-shootings.

[65] The Austronesian supremacist community espouses the belief in Austronesian ethnic superiority – referring to an ethnolinguistic group comprising substantial populations across Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore.

[66] Jonathan Suseno Sarwono, “‘Yup, Another Far-Right Classic’: The Propagation of Far-Right Content on TikTok in Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, November 8, 2023, https://gnet-research.org/2023/11/08/yup-another-far-right-classic-the-propagation-of-far-right-content-on-tiktok-in-malaysia-indonesia-and-the-philippines/.

[67] Saddiq Basha, “The Creeping Influence of the Extreme Right’s Meme Subculture in Southeast Asia’s TikTok Community,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, April 8, 2024, https://gnet-research.org/2024/04/08/the-creeping-influence-of-the-extreme-rights-meme-subculture-in-southeast-asias-tiktok-community/.

[68] “Issuance of Orders Under Internal Security Act (ISA) Against Two Self-Radicalised Singaporean Youths, and Updates on ISA Orders,” Internal Security Department, April 2, 2025, https://www.isd.gov.sg/news-and-resources/issuance-of-orders-under-internal-security-act–isa–against-two-self-radicalised-singaporean-youths–and-updates-on-isa-orders/.

[69] The Sonnenrad, or Black Sun, is a symbol with origins in Nazi Germany which has been appropriated by contemporary far-right and white supremacist movements to evoke ideas of racial purity, Aryan identity and esoteric fascism. For more, see “Sonnenrad,” Anti-Defamation League (ADL), accessed January 7, 2024, https://www.adl.org/resources/hate-symbol/sonnenrad.

[70] Basha, “The Creeping Influence.”

[71] The Philippine Falangist Front (PFF) is a youth-driven, online FRE community based in the Philippines which espouses Falangism, a 20th-century Spanish fascist ideology founded by José Antonio Primo de Rivera, centred on nationalism, authoritarianism and Catholic identity.

[72] Saddiq Basha, “Inside the Philippine Falangist Front: Online Communities as Enablers of Far-Right Extremism in Southeast Asia,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, May 27, 2025, https://gnet-research.org/2025/05/27/inside-the-philippine-falangist-front-online-communities-as-enablers-of-far-right-extremism-in-southeast-asia/.

[73] Ibid.

[74] “Issuance of Restriction Orders Under the Internal Security Act (ISA) Against Two Singaporeans,” Internal Security Department, September 9, 2025, https://www.mha.gov.sg/isd/stay-in-the-know/media-detail/issuance-of-restriction-orders-under-the-internal-security-act-(isa)-against-two-singaporeans/.

[75] Niniek Karmini, “Indonesian Police Investigate Ties Between a Mosque Attack Suspect and Hate Groups,” Associated Press, November 8, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/indonesia-explosions-mosque-school-156c29c591648335bb20d2be13022f2d.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Nirmal Joser et al., “Flash Alert: Student-Perpetrated Bombing at Mosque and School in Jakarta. Authorities Allege Homemade Weapons with References to White-Supremacist Symbols; Officials Be Aware,” The Counterterrorism Group (CTG), November 8, 2025, https://www.counterterrorismgroup.com/post/flash-alert-student-perpetrated-bombing-at-mosque-and-school-in-jakarta-authorities-allege-homemad.